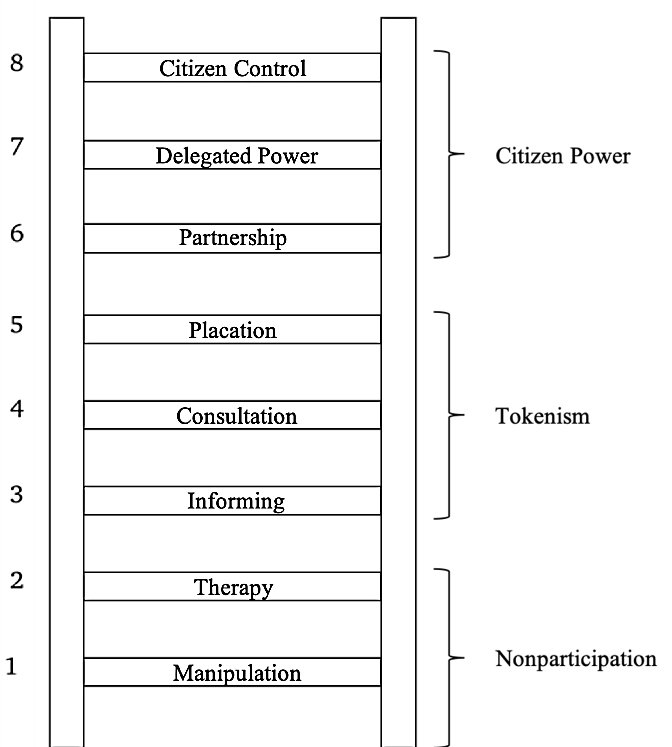

Figure 1. Sh. Arnstein’s “ladder of participation”.

Еlena V. Morozova1 & Anastasiya K. Lomaeva2

Kuban State University. Krasnodar, Russia

Received: 15 May 2022 | Revised: 6 September 2022 | Accepted: 1 October 2022

Abstract

Nowadays, daily life is unimaginable without information and communication technologies (ICTs). “New” reality dictates tectonic changes in communication processes that affect all spheres of life, including political ones. In recent years, there has been a trend towards more open and transparent governance. The purpose of this article is to assess the current status of civic participation platforms in the Russian regions of the Greater Caspian Sea on the basis of a comparative analysis of the institutional foundations and practices of their operation. The main empirical method of the research was the monitoring of civic participation platforms in Astrakhan region, the Republic of Dagestan and the Republic of Kalmykia, as well as qualitative content analysis of the texts posted on the above-mentioned portals. Civic participation platforms have a positive impact on the community. Despite the wide range of opportunities that new technologies offer to engage the party concerned and the citizens, the initiatives fail to achieve the expected results and to mobilize a sufficient number of active users. New forms of interaction between the authorities and civic society are just beginning to develop in our country. The development of electronic civic participation portals in the three Russian regions of the Greater Caspian Sea is taking place in different; their level of development can be estimated as average (in Astrakhan region), below average (in the Republic of Dagestan) and zero (in the Republic of Kalmykia). The main reasons for this state of affairs are digital divide between the regions and the governance practices of the federal and local governments in the regions.

Keywords

E-Democracy; E-Participation; Civic Participation; Political Communication; Internet; Digital Divide

_________________

1Email: morozova_e[at]inbox.ru

2Email: lomaevank[at]ya.ru

_________________

Морозова Елена Васильевна1, Ломаева Анастасия Константиновна2

Кубанский государственный университет. Краснодар, Россия

Рукопись получена: 15 мая 2022 | Пересмотрена: 6 сентября 2022 | Принята: 1 октября 2022

Аннотация

Сегодня повседневную жизнь невозможно представить без информационно-коммуникационных технологий (ИКТ). «Новая» реальность диктует тектонические изменения в процессах коммуникации, которые затрагивают все сферы жизни, в том числе и политическую. В последние годы наметилась тенденция к более открытому и прозрачному управлению. Целью данной статьи является оценка современного состояния платформ гражданского участия в российских регионах Большого Каспия на основе сравнительного анализа институциональных основ и практик их функционирования. Основным эмпирическим методом исследования стал мониторинг платформ гражданского участия в Астраханской области, Республике Дагестан и Республике Калмыкия, а также качественный контент-анализ текстов, размещенных на указанных порталах. Платформы гражданского участия оказывают положительное влияние на сообщество. Несмотря на широкий спектр возможностей для вовлечения заинтересованных сторон и граждан, предлагаемых новыми технологиями, отмечается общая слабость этих инициатив для достижения ожидаемых результатов, мобилизации достаточного числа активных пользователей. Новые формы взаимодействия власти и гражданского общества только начинают развиваться в нашей стране. Развитие порталов электронного гражданского участия в трех российских регионах Большого Каспия происходит разнонаправленно, уровень их развития можно оценить как средний (Астраханская область), ниже среднего (Республика Дагестан) и нулевой уровень (Республика Калмыкия). Основные причины такого состояния – цифровое неравенство регионов и управленческие практики органов государственной власти и местного самоуправления регионов.

Ключевые слова

электронная демократия; электронное участие; гражданское участие; политическая коммуникация; интернет; цифровой разрыв

______________

1Email: morozova_e[at]inbox.ru

2Email: lomaevank[at]ya.ru

______________

In 2011, the United Nations Human Rights Council recognized the right of access to the Internet as a basic human right (Human Rights Council, 2011). The speed of its global coverage is reaching enormous proportions. According to the data of “Digital 2019: Global Internet use accelerates” provided by “We are social” agency, the audience of the Internet grows at the rate of approximately 1,000 users per day. In 2020 it totaled 4.5 billion unique users (Digital 2020: Global Internet use accelerates, 2020).

Today, technology is creating an entirely new generation of forms and tools of public participation that promise to raise the level of public discourse in unprecedented ways, while providing an interactive network environment for decision-making.

New channels of communication allow marginalized groups to be heard. Online interaction reveals a diversity in a society that has always existed but previously had no voice in decision-making.

The most popular view today is that new forms of communication are emerging in the political space through which citizens can obtain important social and political information through access to information and communication technologies.

New forms of interaction between the authorities and civil society are only just beginning to develop in our country. This is particularly the case at the regional level, where examples of the use of e-participation technologies are common but do not always successfully achieve their objectives.

The analysis of Russian and foreign practices, as well as theoretical studies, shows that digital transformation of social and political systems is carried out on the basis of digital platforms integrating economic, social and technological processes, that form digital service ecosystems.

The creation of platforms specifically designed for democratic participation is the key to creating a digital space for political communication. They operate on the basis of people’s motivation to assert their rights, discuss and vote, or simply facilitate access to information and the state. Unlike most other information technology tools (e.g. social networks, portals), the platforms are a space created by the state for comfortable two-way dialogue between the local government and the citizens.

The aim of the study is to assess the implementation practices of civil participation platforms and their current status in the Russian regions of the Greater Caspian Sea.

The concepts of the Information Society (J. Masouda, E. Toffler), Network Public Communication (M. Castells), States as platforms (T. O'Reilly), Participatory Democracy (J. Zimmerman), Electronic Democracy (L. Grossman, A. Etzioni) and digital divide (E. Helsper) were used as the theoretical basis.

The study used the traditional analysis of legal and regulatory instruments of the Russian Federation, which studied the quality of the regional institutions’ of institutional readiness to introduce electronic participation mechanisms, in combination with the analysis of statistical data of Russian scientific and analytical centers: E-government Expertise Centre1, Federal State Statistics Service2, and Unified Interdepartmental Information and Statistics System3. The main empirical method of the research was monitoring civil participation platforms in Astrakhan region, the Republic of Dagestan and the Republic of Kalmykia, as well as qualitative content analysis of texts posted on the above-mentioned portals.

Participation in public and political life has long been recognized as an essential element of democracy and an important expression of civil society. In recent years, various forms of civic engagement have become increasingly important in the debate on the role of public policy openness.

Civic participation is characterized by a variety of forms and an even greater variety of technologies that arise within these forms.

In 1969, American researcher Sherry Arnstein defined civic participation as synonymous with civil governance. That is, the redistribution of power that enables citizens to participate in political, economic and social processes (Arnstein, 1969). He also for the first time systematized eight possible strategies (levels) of citizen participation. For illustration they are represented in the form of a staircase (Sh. Arnstein’s “ladder of participation) (Fig.), where each of the eight steps corresponds to the degree of citizen participation in the final decision:

Manipulation is an “illusory” form of participation, where state institutions, officials or administrators mislead citizens into believing that they are being given power in a process that was deliberately fabricated.

Therapy – Participation as a therapy occurs when government officials and administrators “assume that powerlessness is synonymous with mental illness”, and they create pseudo-programs of participation.

Information Level with no action with Civil society actors. It is one-sided information channels.

Consultation – two-channel channels of communication through which the authorities receive information and feedback fr om citizens come to the fore.

Placation – Participation as appeasement occurs when citizens are given a limited degree of influence in the process, but their participation is largely or entirely symbolic: citizens simply participate to demonstrate that they were involved.

Partnership – Participation as a partnership occurs when government agencies, officials or administrators allow citizens to negotiate better deals, veto decisions, share funding or make requests, which will be partially implemented.

Delegated Power – Participation as a delegation of authority occurs when public agencies, officials or administrators transfer a certain degree of control, management, decision-making or funding to citizens.

Citizen Control – Participation as Civic Control takes place: participants or residents can handle a program or institution, have full political and managerial responsibility and are able to negotiate terms and conditions.

|

Figure 1. Sh. Arnstein’s “ladder of participation”. |

The role of the citizen changes at all stages, fr om the information consumer to the active decision maker. At the latter levels, information and communication technologies support citizens in their willingness to cooperate with the authorities (G2C and C2G) and among themselves (C2C) to develop policies and make decisions.

Today, a more frequent distinction is made between formal (constitutive) and informal (unconstitutional) participation (Müller, 2011).

Formal participation encompasses all forms of legal power to influence decision-making. They vary according to the contemporary forms of democracy. In both direct and representative democracy, participation is linked to the right to vote, so that some groups, such as children, adolescents and migrants, are excluded fr om formal participation. In most cases, procedures in the formal system are regulated by law.

Informal participation permits and allows for the inclusion of some issues of groups that are unable (for example, migrants) or not yet able (for example, children and adolescents) to participate formally in decision-making processes. Informal participation also allows interested groups or the party concerned to contribute, depending on the issue or problem (Müller, 2011).

In this study, “civic participation” is considered (to be) a category that, on the one hand, differs from “political participation”, but on the other hand, cannot be attributed entirely to the non-political sphere. One of the main purposes of civic participation is to influence power and influence decisions taken in public power structures. In this sense it is inseparable from the political process. The forms of such influence are thus integral to the political process.

Today, so-called “digital aborigines”, representatives of digital generations will be the main actors of political life. The term was introduced by Mark Prensky in 2001 (Prenski, 2001). “Digital Aborigines” or “Generation Z” are people born in the mid 1990s – early 2000s, for whom digital environment is the norm. They seek to use their skills in dealing with the new environment to solve socially significant problems. The Internet for the younger generation has become part of the fabric of everyday civic life.

The goal of civic engagement is to improve the standard and quality of life of the community through commitment and motivation. Young people are important actors in civic engagement as they bring new and innovative ideas. Besides, due to the increasing challenges and limited resources to address them, many government leaders recognize the opportunities that Web 2.0 technologies offer not only for the electoral process, but also for improving the quality of life.

Web 2.0 replaced Web 1.0 in 2004. The main differences are the flexibility of web design and the ability to co-create content (Murugesan, n.d.). In other words, Web 2.0 provides an opportunity for people to interact and share their experiences and knowledge. The most relevant technologies created at this stage are blogs, social networking sites of the platform for data exchange and problem solving.

In the digital world, the word “platform” is used to denote the technologies that are the basis for developing applications. It may be hardware or software, an operating system or a web browser with appropriate application programming interfaces.

The term “platform” burst into the political research environment in 2010, when Tim O'Reilly proposed the concept of “States as platforms” (O’Reilly, 2010). O'Reilly emphasizes that “Government 2.0”, like “Web 2.0”, uses technology to better solve collective problems at the city, state, national and international levels. This is much more than the use of social media by government agencies. It’s the transparency of government built through cloud computing, crowdsourcing, mobile applications, and other Web 2.0 by-products that can be applied to government activities.

One of the functions of the platforms is to increase the level of coordination among the users. They are a new open ecosystem that provides dialogue and produces network effects (Jang, 2016).

The implementation of e-participation platforms can help to:

to enable citizens to engage in dialogue with the State;

optimize the flow of information from civil society to the State;

to build an image of a government open to the ideas of its inhabitants.

The Government, as a provider of the platform, creates the necessary infrastructure and major applications that demonstrate the power of the platform, inspires external actors to promote it, and ensures compliance with the “rules of the road”.

The Platform has the potential to create a Government wh ere citizen participation does not end on Election Day. In this model, the Government is the initiator and organizer. This is a radical departure from the model that Donald Kettle described as “the vending machine government”, wh ere “we pay taxes and expect services” (Greve, 2009). If the services we receive don’t meet our expectations, we protest.

Platforms are an important management tool, as they imply that no problem can be solved by one organization alone, and solutions can only be found collectively with motivated participants. A State can provide the basis for a reliable, diverse and sustainable ecosystem of tools and mechanisms to unite efforts in meeting societal challenges.

In 2018, the Center for Strategic Development published a report stating that the goal of the state as a platform is the well-being of citizens and the promotion of technology-based economic growth. The priority is to create conditions conducive to the development of human potential, to the creation of a comfortable and safe environment for human life and to the creation and implementation of innovative technologies (Petrov et al., 2018). As the concept suggests, the development of the State as a platform implies not only passive receipt of public services online, but also the active participation of the citizen in management activities.

In the context of e-government, the web platform should meet the following requirements (Cabrera-Guzman et al., 2020):

compatibility – the platform should be accessible for any type of device using any type of communication based on international standards;

flexibility – the platform must be accessible to any citizen from any place and at any time;

inclusiveness – the platform should be accessible to any citizen with or without physical limitations;

scalability – the platform should have sufficient capacity to process and store data to process every request from citizens;

security – the platform should be based on security standards that ensure authentication, confidentiality, integrity in every transaction between government and citizens.

The development of information and communication technologies in Russia is steadily improving. This is the reason for the illusion that the Internet is ubiquitous in our country. However, it is not. With a steady increase in the number of Internet users in the country, almost a quarter of the population over the age of 12 is still outside the World Wide Web (Mediascope: The Internet Does Not Reach a Quarter of Russians, 2018). Ninety-four per cent of citizens aged between 14 and 23 use the Internet, while in the 54-63 age group the proportion is 37 per cent, while among persons aged over 64 it is 13 per cent (Broadowskaya & Shumilova, 2013). This shows that the proportions of social groups in the virtual world are unequal, which can lead to discrimination in the interests of part of the population.

In addition to the age criterion of digital inequality in Russia, access to the network is uneven in different entities. Despite the relatively low cost of the Internet in Russia compared to other countries, according to “Rostelekom” data for 2017, the average cost of the Internet (up to 10 mb/s) varies from 300 rubles in Voronezh to 1999 rubles in Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky. Also indicative, within the framework of the digital inequality of regions, is the index “Digital Russia” for federal districts. The first place is held by the Ural Federal District with the index of 65.81, which is 1.5 times bigger than the index of the North Caucasus Federal District closing this rating (Index “Digital Russia”..., n.d.).

At the beginning of 2021, the Center for Financial Innovation and Non-cash Economy of the Moscow School of Management “Skolkovo” presented the full version of the rating “Digital Russia” for the subjects of the Russian Federation for the second half of 2020. On a 100-point scale, the interval of “Digital Russia” indices in the second half of 2020 has narrowed and is in the range from 39.2 to 81.14 (in 2019 this interval was 36.06-78.01) (Digital Life of Russian Regions 2020 What Defines Digital Gap?, 2020). This result shows a decrease in the gap between leading and closing rating subjects of the Russian Federation.

To date, feedback platforms based on the Unified Identification and Authentication System have been operating since 2020 in all regions of Russia. At the same time, external regional projects for electronic interaction between power and society are operating successfully in many entities. The large number of different, overlapping services makes it difficult to build a quality dialogue between government and society. Three entities of the Russian Federation belonging to the macro-region of the Greater Caspian Sea were selected to analyze the implementation of civic participation platforms: the Astrakhan Region, the Republic of Dagestan and the Republic of Kalmykia.

These regions are not characterized by a high rate of development and adoption of digital forms of communication in public space. In August 2021, the Ministry of Digital Development, Communications and Mass Communications of the Russian Federation presented a rating of the “digital maturity” of the subjects, which demonstrates the level of progress of the regions within the framework of digital transformation measures. The Astrakhan region is one of the group of subjects with a medium level of digital maturity (values from 50% to 25%). Dagestan and Kalmykia were among the 14 entities whose level of digital maturity was identified as lagging behind (Filatov, 2021).

In November 2020, the digital resource “We the Astrakhans’ started to work in Astrakhan region. According to the Centre for Strategic Analysis and Project Management of Astrakhan Oblast, the idea of the Internet platform was to become an effective mechanism for conveying public opinion to the authorities in the field of urban development in the region. Registration on this platform is possible through a single identification and authentication system, after which all platform services will be available. At this stage, the platform is divided into modules:

voting;

regional News;

surveys;

master plan.

As of 1 September 2021, there are no active votes on the platform. Since 2020, there have been 5 votes on the platform on the improvement of public spaces in Astrakhan. There is no survey information on the portal. The news module is operational and highlights implemented initiatives for urban improvement in the region.

The big project on the platform was the discussion of the master plan of the Astrakhan agglomeration. Any authorized user from 1 to 31 August 2021 had the opportunity to send his initiatives and suggestions, ask questions and make comments.

The platform “We the Astrakhans” has good potential and functionality covering all levels of civic participation (from information to control), but the platform interface does not allow to assess the degree of citizen involvement. It is worth noting that the platform does not have information support, which hinders the introduction and popularization of electronic communication mechanisms in the region.

In the Republic of Dagestan in 2019 the platform “Active Citizen” was launched, analogous to the platform of electronic interaction of Moscow. Every inhabitant of the Republic of Dagestan had the opportunity to vote on various topics. Later, in parallel with the platform “Active Citizen”, the digital resource “My Dagestan” was launched. It was intended to be a platform for monitoring the implementation of priority projects of the Republic. The key project on the portal was the “Interactive Map”, wh ere priority projects were marked, clicking on which it was possible to get detailed information.

It is noteworthy that as of September 2021 the platform “Active Citizen” does not function, and the platform “My Dagestan” has stopped performing tasks that were assigned to it at the start. With the arrival of the pandemic, “My Dagestan” became an information resource about COVID-19. On-line information is provided on vaccinations (percentage of those vaccinated, number of vaccines allocated) throughout the Republic. The news part of the portal has not been updated since May 2021.

Thus, to date, there is no operational platform for real electronic interaction between the authorities and civil society in the Republic of Dagestan.

The Republic of Kalmykia is currently lagging behind Astrakhan region and the Republic of Dagestan in the development of electronic civic participation platforms. To date, there is no civic engagement platform in the region, and there are few electronic communication channels. They are developed only at the first stage of e-participation and consist in informing the public through Internet resources. The only two-way channel of communication is the Internet in the Head of the Region reception room. Such a channel does not respond to the trend of modern communications in the information and communication environment.

The development of civil participation platforms in the regions faces a number of obstacles:

low level of involvement of citizens in determining the development of State;

shortage of information on the results and contributions to public objectives.

As a result, the State makes decisions on limited vision and sometimes does not know the real needs of citizens at all. Many web-based platforms created by the State or local authorities do not contain elements to establish a real link between the authorities and civil society.

The analysis of electronic cooperation practices in the constituent entities of the Russian Federation in the Caspian Sea region has shown that the level of development of civil participation platforms is low. The real functioning platform exists only in the Astrakhan region. There is lack of involvement not only of citizens but also of the authorities into electronic communication processes. Platforms functionality which should cover all levels of civic engagement (from information to monitoring) is not well developed. The management practices of the State authorities and local governments of the regions, the underestimation of the role and prospects of the digitization of the public sphere are one of the reasons for this state of affairs. The main reason, according to the authors, is the digital divide between regions, at all three levels: access, digital skills and motivation.

The paper was written by two authors who were equally involved in theoretical analysis of the problem and in the conduct of research. Anastasiya K. Lomaeva has collected and processed empirical data. Еlena V. Morozova has interpreted the results and contributed to scientific editing of the article.

The study was carried out by a grant from the Russian Science Foundation No. 22-18-00301 «The process of constructing new identities in the Caspian macroregion in the context of societal security».

Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A Ladder of Citizen Participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

Broadowskaya, E. V., & Shumilova, O. E. (2013). Russian users and non-users: Ratio and main features. Monitoring Public Opinion: Economic and Social Change, 3, 5–18.

Cabrera-Guzman, J. L., Villaverde-Hidalgo, L. C., Parra-Michel, J. R., & Martínez-Peláez, R. (2020). A Web-Based Platform Prototype to Enhance e-Participation and e-Transparency in Local Government. ICDS 2020 : The Fourteenth International Conference on Digital Society, 4, 61–66.

Digital 2020: Global Internet use accelerates: (n.d.). We are social. https://wearesocial.com/2020/79/4830.pdf

Digital life of Russian Regions 2020 what defines digital gap? (2020). SKOLKOVO Institute for Emerging Market Studies (IEMS). https://iems.skolkovo.ru/downloads/documents/SKOLKOVO_IEMS/Research_Reports/SKOLKOVO_IEMS_Research_Digital_life_of_russian_regions_2020-06-09_ru.pdf

Filatov, A. (2021, August 12). 9 regions have reached a high level of digital maturity—MinTsifry. Digital Russia. https://d-russia.ru/vysokogo-urovnja-cifrovoj-zrelosti-dostigli-9-regionov-mincifry.html

Greve, C. (2009). The Next Government of the United States: Why Our Institutions Fail Us and How to Fix Them. Public Management Review, 11(4), 541–542. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030903030963

Human Rights Council (2011). Resolution 20/8 of 16 May 2011. United Nations, Human Rights Council. https://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/docs/17session/A.HRC.17.27_en.pdf

Index “Digital Russia”. Image of the digitization of the constituent entities of the Russian Federation through the prism of open sources (pp. 8392–1070118). (n.d.). http://finance.skolkovo.ru/jfhsk_?8392-1070118

Jang, S. H. (2016). A Comparative Study on the Development of K-MOOC Platform. Journal of Platform Technology, 4(1), 33-38.

Mediascope: The Internet does not reach a quarter of Russians. (2018, April 19). Sostav.Ru - Advertising and Marketing News. https://www.sostav.ru/publication/mediascope-internetom-ne-okhvachena-chetvert-rossiyan-31282.html

Müller, E. (2011). Public Participation Manual. http://www.alpine-space.org/20072013/uploads/tx_txrunningprojects/Demochange_Public_Participation_Manual.pdf

Murugesan, S. (n.d.). Handbook of Research on Web 2.0, 3.0, and X.0: Technologies. Business, and Social Applications. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-60566-384-5

O’Reilly, T. (2010). Government as a Platform. In Open Government: Collaboration, Transparency, and Participation in Practice (pp. 11–40). O’Reilly Media.

Petrov, M., Burov, V., Sharov, A., & Shklyaruk, M. (2018). “The State as a Platform” Cyber State for the Digital Economy. Digital Transformation. Center for Strategic Development. https://wwww.csr.ru/upload/iblock/313/3132b2de9ccef0db1eecd56071b98f5f.pdf (In Russian)

Prenski, M. (n.d.). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. https://gimc.ru/content/statya-marka-prenski-aborigeny-i-immigranty-civofrogo-gomira9

Schugurensky, D., & Myers, J. P. (2008). Informal Civic Learning Through Engagement in Local Democracy: The Case of the Seniors’ Task Force of Healthy City Toronto. In K. Church, N. Bascia, & E. Shragge (Eds.), Learning through Community (pp. 73–95). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6654-2_5

Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A Ladder of Citizen Participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

Cabrera-Guzman, J. L., Villaverde-Hidalgo, L. C., Parra-Michel, J. R., & Martínez-Peláez, R. (2020). A Web-Based Platform Prototype to Enhance e-Participation and e-Transparency in Local Government. ICDS 2020 : The Fourteenth International Conference on Digital Society, 4, 61–66.

Digital 2020: Global Internet use accelerates: (n. d.). We are social. https://wearesocial.com/2020/79/4830.pdf

Greve, C. (2009). The Next Government of the United States: Why Our Institutions Fail Us and How to Fix Them. Public Management Review, 11(4), 541–542. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030903030963

Human Rights Council (2011). Resolution 20/8 of 16 May 2011. United Nations, Human Rights Council. https://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/docs/17session/A.HRC.17.27_en.pdf

Jang, S. H. (2016). A Comparative Study on the Development of K-MOOC Platform. Journal of Platform Technology, 4(1), 33-38,.

Mediascope: Интернетом не охвачена четверть россиян. (2018, апрель 19). Sostav.ru – новости рекламы и маркетинга. https://www.sostav.ru/publication/mediascope-internetom-ne-okhvachena-chetvert-rossiyan-31282.html

Müller, E. (2011). Public Participation Manual. http://www.alpine-space.org/20072013/uploads/tx_txrunningprojects/Demochange_Public_Participation_Manual.pdf

Murugesan, S. (б. д.). Handbook of Research on Web 2.0, 3.0, and X.0: Technologies. Business, and Social Applications. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-60566-384-5

O’Reilly, T. (2010). Government as a Platform. В Open Government: Collaboration, Transparency, and Participation in Practice (pp. 11–40). O’Reilly Media.

Prenski, M. (б. д.). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. https://gimc.ru/content/statya-marka-prenski-aborigeny-i-immigranty-civofrogo-gomira9

Schugurensky, D., & Myers, J. P. (2008). Informal Civic Learning Through Engagement in Local Democracy: The Case of the Seniors’ Task Force of Healthy City Toronto. В K. Church, N. Bascia, & E. Shragge (Eds.), Learning through Community (pp. 73–95). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6654-2_5

Бродовская, Е. В., & Шумилова, О. Е. (2013). Российские пользователи и непользователи: Соотношение и основные особенности. Мониторинг общественного мнения: экономические и социальные перемены, 3, 005–018.

Петров, М., Буров, В., Шаров, А., & Шклярук, М. (2018). Государство как платформа. (Кибер) государство для цифровой экономики. https://www.csr.ru/upload/iblock/313/3132b2de9ccef0db1eecd56071b98f5f.pdf

Филатов, А. (2021, август 12). Высокого уровня цифровой зрелости достигли 9 регионов—Минцифры. Digital Russia. https://d-russia.ru/vysokogo-urovnja-cifrovoj-zrelosti-dostigli-9-regionov-mincifry.html

Цифровая жизнь российских регионов 2020: Что определяет цифровой разрыв? (б. д.). Институт исследований развивающихся рынков бизнес-школы СКОЛКОВО (IEMS). https://iems.skolkovo.ru/downloads/documents/SKOLKOVO_IEMS/Research_Reports/SKOLKOVO_IEMS_Research_Digital_life_of_russian_regions_2020-06-09_ru.pdf

_______________________________

1E-State Expertise Center. https://d-russia.ru/

2Federal State Statistics Service. Official Website. https://rosstat.gov.ru

3Integrated interdepartmental statistical information system. Official Website. https://fedstat.ru