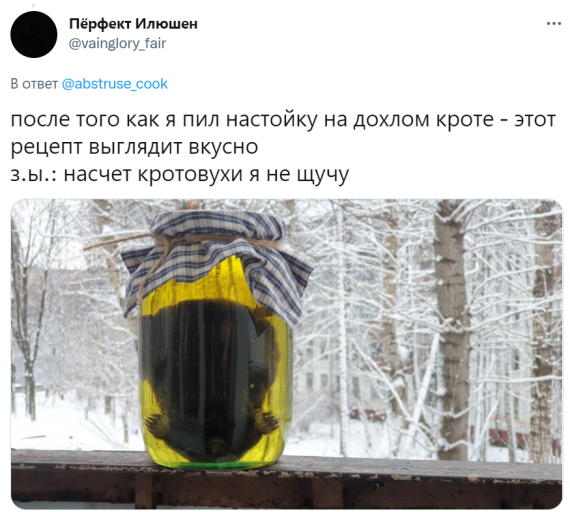

Fig. 1. Screenshot of the Twitter feed Translation: After drinking a dead mole tincture this recipe looks delicious. P.S. I’m not kidding about krotovukha

Elena E. Zavyalova

Astrakhan State University. Astrakhan, Russia. Email: zavyalovaelena[at]mail.ru

Received: 10 January 2023 | Revised: 1 February 2023 | Accepted: 15 February 2023

Abstract

The subject of the study was one of the most viral Russian trends of the turn of 2022–2023: krotovukha, a tincture on a dead mole, which attracted attention of not only the Internet users, but also of doctors, restaurateurs, historians, and legislators. The aim of the research was to identify the reasons for active participation in communication on such a topic. It was found that the image of the mole is very much in demand in world culture. This is due to its otherness, its ability to act, to change space, to link the underworld with the mundane. Analysis of a video by an alcohol blogger fr om Moscow revealed the presence of initiation semantics attached to tasting. These types of publications become a modified version of the ritualised round drinking, as evidenced by patriotic themes and masculine accessories. The name itself already potentially contains the semantics of the familiar, the expressive, and the dearly beloved. A large number of memes demonstrate the strength of user reactions to krotovukha. The most comical effect is produced by stylistic disruption. The incredible effects of the “national” elixir are played off. The duality of perception of the character and the drink made fr om his body makes the recognisable image variable, polyvalent, and suitable for multiple transformations. The article concludes by noting that the recipe that went viral reflects a belief in sympathetic magic, the ritual power of sacrifice and the cosmogonic significance of the rite – the sacred timing of information dissemination.

Keywords

Mole; Trickster; Meme; Viral Content; Alcoblogger; Initiation; Sacrifice; Sympathetic Magic; National Tradition; Masculinity

Завьялова Елена Евгеньевна

Астраханский государственный университет им. В.Н. Татищева. Астрахань, Россия. Email: zavyalovaelena[at]mail.ru

Рукопись получена: 10 января 2023 | Пересмотрена: 1 февраля 2023 | Принята: 15 февраля 2023

Аннотация

Объектом настоящего исследования явился один из самых вирусных российских трендов рубежа 2022–2023 годов – кротовуха, спиртовая настойка на мёртвом кроте, которая обратила на себя внимание не только завсегдатаев сетевых ресурсов, но и медиков, рестораторов, историков, депутатов. Целью разысканий стало определение причин активной вовлечённости в коммуникацию на такую тему. Было установлено, что образ крота весьма востребован в мировой культуре. Это связано с его инаковостью, способностью действовать, изменять пространство, связывать подземный мир с надземным, потусторонний с обыденным. Анализ видеоролика московского алкоблогера ютуб-канала “Alcorithmˮ показал наличие семантики инициации, придаваемой дегустации. Подобного типа записи становятся модифицированным вариантом ритуализированного питья вкруговую, что подтверждается патриотической тематикой и маскулинными аксессуарами. «Правильный» напиток помогает структурировать социальное пространство «своих». В самом названии уже потенциально содержится семантика фамильярного, экспрессивного, родного. О силе реакции пользователей на кротовуху свидетельствует большое количество мемов. Поднятый персонажем кубок / фужер / иной сосуд становится триггером, подталкивая к актуальной его «корректировке». Наиболее комичный эффект создают нарушения стилистического единства, когда в цельный, до мелочей выстроенный художественный образ вносится чужеродный элемент. Обыгрывается невероятная эффектность действия «национального» элексира. Частотны случаи использования кадров из отечественных мультфильмов. Двойственность восприятия персонажа и напитка, приготовленного из его тушки, сделала узнаваемый образ вариабельным, поливалентным, удобным для множественных трансформаций. В заключении делается вывод, что в разлетевшемся по сетям рецепте слышны отзвуки веры в симпатическую магию, ритуальную силу жертвоприношений, а также в космогоническое значение обряда – здесь свою роль играет сакральное время распространения информации.

Ключевые слова

крот; трикстер; мем; виральный контент; алкоблогер; инициация; жертвоприношение; симпатическая магия; национальная традиция; маскулинность

The subject of this study was one of the most viral Russian trends of the turn of 2022–2023: krotovukha, also known as mole tincture. Almost everything is discussed on social media – if only there were like-minded people. Discussions about spirits are popular, but this one was remarkable in every way.

On 7 December 2022, on Twitter, which is currently blocked in Russia, a user nicknamed Zaumnyi povariuga (English: Brainy Chef, Russian: Заумный поварюга) described the medieval way of making ale with a cock brewed in it. This was probably the famous recipe for English cock ale fr om Sir Kenelme Digbie’s cookery book (The Closet..., 2001). In response to this post, user nicknamed Perfect Illusion (Russian: Пёрфект Илюшен) revealed that he had tried an even more specific drink – a tincture on a dead mole. To prove it, the tweet included a photo of a jar styled as rustic jarred food, and it got a lot of likes.

|

Fig. 1. Screenshot of the Twitter feed Translation: After drinking a dead mole tincture this recipe looks delicious. P.S. I’m not kidding about krotovukha |

Three days later, Perfect Illusion posted the details on the thread: “It tastes and smells like alcohol and stale earth after a rain in a deciduous forest. Generally pleasant, but not good for a city dweller”. Allegedly, his friends made the drink as a joke and presented it to the user, and he and several others dared to try it. A link to the video of his friend Dmitry tasting the mole tincture on his YouTube channel convinced many sceptics of the credibility of the information.

The information quickly spread among the Russian-speaking users of the platform and went beyond its borders. Other social networks were quick to respond to the “word of the day”. Quatrains, haikus, songs, jokes, puns, video parodies, a Minecraft Texture Pack variant, and a huge number of memes on the topic appeared. ChatGPT, a neural network based chatbot, generated a horror film script, Midjourney created the poster and the first footage of the horror film.

Krotovukha has been successfully offline since mid-December. The details of the recipe, the medicinal properties of the drink and its analogues were analysed. The discussion included distillers, restaurateurs, psychologists, historians, and doctors. Rospotrebnadzor – Russian service responsible for the supervision of consumer rights protection and human wellbeing – was dismayed to print an article about parasites living in moles and the ineffectiveness of alcohol-based protection against zoonotic and helminthic pathogens. Several regional health ministries have issued warnings about the dangers of the drink. Narcologist Odintsova urged parents to talk to their young offspring when they “go looking for the dead mole in December” (“Talk to…” 2022). State Duma’s legislators Burmatov and Kurinniy promised all the tasters to put them in jail for killing the animal and publishing the “cruel act” on the Internet (“State Duma’s legislator…” 2022).

Meanwhile, online clothing shops have quickly set up the production of T‑shirts with the most topical print. It is now possible to order a teapot in the shape of a jarred mole on Avito, while Yarmarka Masterov offers a souvenir filled with hypoallergenic synthetic fiber. One designated website offered a kit to make the drink “using the original recipe”. Another one offered an online game with a mole farm, a planet, and a galaxy. Businessman Semyonov has registered the trademark Krotovukha.

Let us try to understand the reasons for active participation in communication on such an issue.

|

Fig. 2. T-shirt with a fashionable print |

|

Fig. 3. A flight mask made fr om mole fur |

The beastie which lives in close proximity to humans and is phenomenally mysterious, has long captured human imagination. Its disproportionate forelimbs, lack of a neck, proboscis-like nose, 44 teeth and enormous appetite have earned it the nickname The Underground Crocodile. For most Russians (and not only Russians) it is exorbitantly funny; for the others it is disgusting. Its small size and fragile body make it easy prey for dogs, cats, and disgruntled lawn and garden enthusiasts who find it difficult to put up with this restless creature’s “fighting spirit”.

The mole does not eat plant food, but burrows underground so vigorously that it disrupts root systems and damages sewage pipes and power cables. “Numerous mole holes reduce pasture productivity, lead to <...> damage to agricultural machinery during mechanised harvesting” (Yakovlev & Babich, 2015, p. 234). It also happens to be a pretty good fur material. Initially, it was used to make high-quality masks for pilots. In Soviet times, it was used to sew mud-repellent fur garments (ibid). Until the 1980s, there were special procurement offices, and even schoolchildren were obliged to catch these pests. On average, 200–300 pelts were needed for a carpet and up to 4,000 for a fur coat. Today, you can buy one for around €5,000.

Its place in space, its behaviour and its appearance made it a chthonic animal. This, according to A. Gura, is manifested in the border position between animals and “creepers”, in the symbolism of “blindness and rejection of sunlight, in omens foretelling death, in the symbolic correlation of a molehill with a grave, etc.” (1995, p. 682). People decided that a dead body hung upside down1 could, for example, protect pets and bring rain (ibid).

Separately, the “healing” properties of the animal should be mentioned. M. Hamer (2019) writes: “Moles and magical rituals seem to be inseparable. Mole catchers know that a pair of dried mole claws prevents the development of rheumatism and protects against misfortune. This is a popular belief throughout Europe. And if you hold the mole in your hands until it dies, you will acquire the gift of healing. Different parts of the mole can cure epilepsy, prevent toothache and fever, relieve cramps and remove warts” (p. 14). The claws, hearts and teeth of the mole were popular with healers, and there was a rule that organs should be taken fr om a living mammal. An evil way of treating stomach pains was to tear the mole above the patient’s stomach, then smear blood on it and place the remains on the patient’s navel (Gura, 1995, p. 684).

There is no point in listing such “recipes”. What is important is that, judging from the folklore archives of recent decades, similar methods are still being practiced. This is particularly evident in the recordings made in Kuban' by M. Sementsov (2003). It is believed that the death of a mole still has miraculous might. To gain healing powers, an animal must be strangled in a certain way (there is a special incantation, its own subtleties of killing, etc.). The fingers used to kill the animal are then used to heal the sick.

In non-ritual folklore, there are stories that explain the origin of the mole’s two distinctive characteristics: “blindness” and an underground lifestyle. In Russia, for example, there is a legend of an animal being blinded by God as punishment for working on the Christian holiday of the Annunciation. To get his eyes back, he has to dig “as many holes as there are stars in the sky” (Gura, 1995, p. 683). In Belarus', the creature was punished for the damage done to the Garden of Eden. The outward resemblance of the animal’s forelimbs to the palms of the hands of humans led to stories of people turning into moles because of land disputes, fraudulent surveying, ploughing at taboo times, etc.

The mole was a subject of interest to ancient thinkers. Aristotle (1996) described it in his History of Animals. According to S. Naranovich (2021), the philosopher deliberately emphasises metaphysical blindness. For the ancient Roman erudite Pliny the Elder, the ability of mammals to inhabit the soil is a clear evidence of the existence of a “life-giving breath” (spiritus vitalis, vitalis halitus) circulating in the universe (1995, p. 165). The analogy of the work of a mole is used to describe the nature of earthquakes by the ancient Greek geographer Pausanias (1996, XXIV, 6). And the physician Galen of Pergamon compares the “imperfect eyes” of these insect-eaters, which resemble the embryonic visual organ of other vertebrates, to the “fertile parts of a woman” (1971, p. 159–162), which are underdeveloped in comparison to the male.

In classical literature, the mole appears more often in figurative comparisons. A textbook example is Hamlet’s line to his father’s phantom, whose voice comes from underground:

“Well said, old mole. Canst work i’th’ earth so fast?

A worthy pioneer!ˮ (Shakespeare, 1917, p. 34).

The animal’s restlessness becomes a symbol of invisible but ceaseless work, of daring endeavour. G. Hegel used Shakespearean imagery to refer to the idea of the eternal movement of the world spirit (Weltgeist): “To its onslaught – when the mole in the depths continues to dig – we must listen in order to extract the truth” (1932, p. 691). A. Herzen introduces a quotation that proves the inevitability of social change: “But decomposition took its course, the ‘underground mole’ worked tirelessly” (1955, p. 113). K. Marx, on the imminent political upheaval: “And when the revolution has finished this second half of its preliminary work, Europe will rise from its seat and say, triumphantly: ‘You dug well, old mole!’” (Marx & Engels, 1957, p. 205). This fragment was quoted by Lenin in his book The State and the Revolution (1962, p. 27).

Our aim is not to find as many mentions of the extraordinary creature as possible. It is important to show how wide the range of interpretations of the image is – and how deep these interpretations go. The following two possibilities are particularly illustrative. The preacher John of Kronstadt (Ioann Sergiev), in his spiritual exhortation My Life in Christ, compares instinctive motives to moles: “Watch yourselves – your passions especially – in your home life, wh ere they appear freely, like moles in a safe place. Outside our own home, some of our passions are usually screened by other more decorous passions, while at home there is no possibility of driving away these black moles that undermine the integrity of our soul” (2008, p. 49). In his sonnet “The Mole”, the Symbolist poet Balmont declared his love for this creature whose way of life is so unusual. He depicts the character’s underground home as a mysterious castle:

Down in the depths, wh ere there are alleys for sure,

And ghosts of black towers and courtyards,

Where strange midnight feasts are held… (1921, p. 78).

The place is the centre of an unattainable dream, and its inhabitant becomes the alter ego of a restless, defenseless author, cut off from the real world.

The mole is more common in works for children. The reason for this seems to lie in the fact that it is different from other members of the animal kingdom and represents a separate habitat. For example, the main characters in Grahame’s story The Wind in the Willows (1908) are Mole, Badger, Mr. Toad, and Ratty (a water rat). In Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale (1835), the mole is a negative character. However, he is portrayed rather ambiguously: he falls in love with Thumbelina after she sings her songs, digs a gallery for the neighbours to walk in, and acts as a gallant gentleman2. In a number of cases, the mole acts as a “non-magical” helper: for example, he tells Pinocchio who stole the puppets from the cave (Aleksey Tolstoy’s fairy tale, 1937); he helps Cipollino and his friends several times (Rodari’s fairy tale, 1951–1957). In most children’s stories – be it literary, animated or cinematographic – the mole is included in the crowd, along with other inhabitants of the forest (field, steppe), as an example of a kind of animal inclusion.

Perhaps the most famous mole is Krtek (1957–2002) from the Czech cartoon series created by Zdeněk Miler. According to the artist, it took a long time to choose a character, as the author wanted to find an original animal that had not appeared as a protagonist before (Vasinkevich & Kukhineva, 2021). Krtek is curious, sweet, and kind. He stands out among his friends for his agility, ingenuity, technical awareness, and ability to use the achievements of civilization – from spindle and cutlery to umbrella and obstetric stethoscope. The stark contrast between Krtek and the other characters, the mouse, the rabbit, and the hedgehog, is particularly evident in the series “Krtek na dovolenéˮ (“The Little Mole on Vacation”, 1995). He often acts as a mythological cultural figure, showing other protagonists the joys of an orderly world, be it a Christmas tree or a chamomile infusion. At the same time, he fights against environmental injustice.

|

Fig 4. A frame from the cartoon series by Zdeněk Miler |

At the end of a brief overview of the possibilities for presenting the desired image, another character should be mentioned. In 1989, the short tale The Story of the Little Mole Who Knew it Was None of His Business by the German writer Hans Werner V. Holzwarth was published. The little book went on to become an international bestseller and was translated into more than 30 languages3. The plot of the work is based on a detective story which, for the sake of scientific accuracy, should be reproduced in its entirety. The mole travels across the surface of the earth in search of the creature that has relieved itself on mole’s head when the latter came out of his hole to watch the sunrise. The pigeon, the horse, the hare, the goat, the cow, and the pig that he met along the way do not simply declare their innocence, but provide evidence. The reader is forced to learn in detail – and thanks to the many sound imitations – how different the defecation process is for each of them, and what their excrement looks like. According to the canon of fairy tales, all ends well. The flies help the protagonist – they carry out organoleptic tests and establish the dog’s guilt. The mole drops his load on the wrongdoer and returns home, relieved. The public success of the book is symptomatic; some reviewers have suggested that the work opens up a special genre that legalises the subject of natural functions4. Among its merits, critics point to its cognitive-scientific potential, its positivistic approach, and its humanistic orientation. What is important to us in the context of our topic is another modification of the image of the animal. Seen through the prism of mythological thought, the mole in such a delicate situation is revealed in its chthonic milieu. In a casual sense – he is once again presented as a resentful creature.

As one can see, the image of the mole turns out to be very popular in world culture. The main reasons for this are its otherness, its ability to act, to change space, to link the underworld with the mundane, the otherworldly with the ordinary.

For most peoples, drinking alcohol is an ancient cultural tradition (Song, 2015, p. 3). In the West, the discovery of distilled alcohol was attributed to alchemists, and the efficacy of the drink led esoterists to believe that the end of the world was near (Matheson, 1985). The ancient Slavs had mainly low-alcoholic fermented beverages (mead, kvass, birch sap wine) and from the ninth century — the “status” wine (Boguslavsky, 2004, p. 150). By the fifteenth century, the method of evaporating the liquid had become popular. Peter the Great and his closest followers contributed to expanding the range of strong drinks in Russia, desacralising their consumption and securing the state monopoly on distillation. Old Russian restrictions on the consumption of alcoholic beverages were abolished. However, alcohol continued to be associated with a special event, a celebration or at least mental relaxation (Chukhrova & Savitzkaja, 2012, p. 226).

Since ancient times, it has been a male prerogative to drink a lot and still be able to control oneself. Moreover, in certain situations, drinking was considered obligatory for men. In his Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow, A. Radishchev noted gender and ethnic stereotypes in alcohol consumption: “Look at a Russian and you will find him brooding. When he wants to get rid of his boredom, or as he himself puts it, when he wants to have some fun, he goes to a tavern. <...> The burlak, who goes to the tavern with his head hanging down and comes back covered in blood after being slapped in the face, can solve many things in Russian history that have hitherto been guessed at” (“On the corruption…”, 1983, p. 112). Classical literature of the Romantic era canonised bacchic motifs, which became inseparable from love and freedom – “or rather, formed an organic part of them” (Gukovsky, 1965, p. 217). According to V. Lovchev, by the mid-19th century, alcohol “had established itself in the leading spheres of Russian intellectual culture (literature, painting, music), the images formed at that time... still exist today” (2012, p. 101).

|

Fig 5. A meme made from a photo by youtuber Apetor |

Despite significant political changes in twentieth-century Russia, there were no tangible advances in the practice of drinking. “...Until the mid-1970s, smoking and alcohol consumption in our country were considered to be dabbling, and even in official documents they are often referred to by the mild Soviet-era combination of the words ‘bad habit’. <…> Even in the minds of children, tobacco and alcohol have become standard attributes of men” (Demin & others, 2012, p. 51). Not all of the government anti-alcohol policies adopted at the end of the 20th century and in the first decades of the 21st century have been as effective as one would wish. At least 70 % of annual per capita consumption in Russia, unlike in the vast majority of other countries, is of spirits (“Alcohol and Drinking Culture…”, 2015). Today, their popularity is clearly demonstrated by the krotovukha phenomenon.

The Moscow alcoblogger on the Alcorithm YouTube channel has been reviewing drinks over the years, from hawthorn tincture and port wine 777 to Hennessy Library, Metaxa, and Jack Daniels. Dressed in a sweatshirt, long sleeve, T-shirt, muscle tank top; with hair in a ponytail and with a headband, with a chub, with curls; in the kitchen, in the park, in the countryside; alone, with the dog, with friends… During the taster sessions, Dmitry demonstrated the qualities of a successful blogger: openness, naturalness, observation, a sense of humour and the ability to communicate his thoughts and message. But the videos did not cause a great deal of excitement. However, all that changed on 9 May 2021, when he told the viewers about krotovukha.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 6, 7, 8, 9. Footage of the blogger’s reviews on the Alcorithm YouTube channel |

Indeed, the impressive composition of the drink played a decisive role. However, a comparison of the May video with others suggests that the preparation for the presentation was unparalleled. This is evidenced by the significant change in the molellier’s5 appearance and the unfamiliar surroundings. Dmitry has a new haircut and is dressed in camouflage. He is sitting on a sofa in a room. In front of him there is a small folding table covered with newspapers. The blogger admits to gluing a wooden model of the PPSh, a Soviet submachine-gun designed by Georgy Shpagin in 1940, before the recording began. The model is in the background, in an open box on the windowsill; a few tools (pliers, file, and a screwdriver) and glue are on the table. There is also a “bachelor’s snack”: processed cheese, sausage, sprats, spring onions, cucumber, tomatoes, and bread. The unopened bottle of cognac seems to have a distracting function.

After mentioning the “noble” drinks made from plants and berries, Dmitry goes on to talk about exotic tinctures made from “formerly living creatures”. And then he proudly declares: “We are no country bumpkins”. He calls krotovukha “a drink full of existential horror and pain” and almost genuinely wonders how the Russians came up with the idea of making it. A detailed recipe follows, including a description of the correct degree of hardness of the “raw material”, the age of the victim, its position in the jar, the type of liquid to be poured and the length of the infusion. The blogger emphasises the drink’s medicinal properties, but also advises caution in consumption. The video culminates in a tasting session in which the young man shares his thoughts on the colour, smell and taste of the drink, as well as the quality of the intoxication that ensues. The drink is clearly strong and not very pleasant – as the audience can distinctly tell from Dmitry’s blurry gaze and the tense muscles of his face. Consuming the drink is an ordeal, and in the video, it obviously takes on the semantics of initiation.

The video has a strong thematic character. This is evidenced by references to the Victory Day celebrations over the Nazi invaders, to the hero cities of Moscow, the place wh ere the record was made, and to Murmansk, the place wh ere the brother – yes, the brother – lives6. After sipping krotovukha, Dmitry drinks a beer from a plastic bottle and smokes, trying to hold a cigarette between his forefinger and thumb, just like at the frontline. Clothes, tools and newspapers, a model gun, cut glass, food, a pack of Belomor ciggies with matches – all is intended to create the image of a manly man – experienced, reliable, skillful and prudent.

Another important point is the unobtrusive national flair, which has been absent from previous reviews. This is created by a homespun runner on the windowsill, a Soviet-style beer mug, a decorative rag wrapped in string around a jar (with a plain polythene lid underneath). The result is a conclusion about the difference between “the orthodox Russian krotovukha and the repulsive snake vodka”. “The ‘right’ drink helps to structure the social space of ‘soulmates’”. The whole set of the brutal, the patriotic, and the vintage aims to inspire confidence in the information and appreciate the pleasures of a strong tincture. We dare suggest that this kind of blogging tasting is a modified version of the ritualised round drinking, the purpose of which was to engage with the clan (Bayburin & Toporkov, 1990, p. 80).

A photo posted in December 2022 by Perfect Illusion is in a similar style. The same rustic rag and string on the glass (possibly the same jar) on the concrete balcony railing. A spectacular angle to see the animal’s body in full view. And the background used as context: a typical large courtyard between blocks of flats with snow-covered trees. The setting (Russian winter) interacts with the main subject, enhancing the meaning of the frame.

In this respect, the name of the drink is also remarkable. The lexeme “krotovukha” (Russian: кротовуха) was created by analogy with existing colloquialisms typical of Slavic languages (e.g. medovukha, Russian: медовуха, a honey-based alcoholic beverage; khrenovukha, Russian: хреновуха, a horseradish-based alcoholic beverage, etc.). The suffix -ух- (romanized: -ukh-), when added to different parts of speech, forms stylistically reduced synonyms for the nouns from which they are formed (Efremova, 1996, p. 482, 502). That means that the name already potentially contains the semantics of something familiar, expressive, related7.

Food culture shapes stereotypes based on ethnic, social, and gender identity (Yakushenkov & Song Jie, 2015, p. 248). Krotovukha, organically and ironically, combines all these components of advertising focus that R. Barthes (2013, p. 23–24) once highlighted, namely national idea, status, and health.

As mentioned above, the strength of the user reaction to krotovukha is evidenced by the number of memes. We counted them and found that there were more than 250. In attempting to typologise the flow, we set out to discover common trends in the process of absorbing content with a national theme. A word of warning: most of the images were already memes and, thanks to online generators, were easily changed to suit the latest news.

Of course, in the “repository of cultural codes of the network community” (as defined by N. Marchenko (2013, p. 113)), the leader is a photograph, a frame, a picture of the drink with an alcohol theme. A goblet, glass or any other vessel raised by a character becomes a trigger, prompting an actual “adjustment”. The most comical effect is produced by stylistic disruption, when an alien element is introduced into a coherent, carefully constructed artistic image.

|

Fig. 10. A meme based on a frame from Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby. Translation: The world is a mess Meanwhile people on Twitter: KROTOVUKHA |

Unsurprisingly, several people did not conspire to “hand” the elegant Leo DiCaprio a jar of krotovukha in at least three historically costumed versions: the drink is used to substitute champagne (Titanic, 1997), a coconut drink (Django Unchained, 2012), and a martini (The Great Gatsby, 2013). Creative social media users could not help but use the actor’s brilliant way of holding the glass and his ability to express a rich palette of emotions with his face.

The improvisations on the themes of other well-known films are less striking, but are still a clear success: Indiana Jones & The Last Crusade (1989), Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest (2006), Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door (2007), Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince (2009), Fury (2014), Druk (2020), etc. Each author chooses a topic according to the age and interests.

Often krotovukha is put in the place of a mysterious substance, a secret scientific composition: Aliens (1986), The Matrix (1999), Spider-Man (2002), Prometheus (2012), Blade Runner 2049 (2017), The Mandalorian (Season 2, 2020). Sometimes the drink is simply a substitute for some kind of liquid, a forbidden potion: Perfume: The Story of a Murderer (2006), The Shape of Water (2017), Breaking Bad (2008–2013). They play on the incredible effects of the “national” drink.

The widespread popularity of computer games has long made images from them the material for memes aimed at a very wide audience. The youth’s active interest in the krotovukha phenomenon is clearly demonstrated by numerous images from the multiplatform game The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim (2011), screenshots from the survival horror genre, Space Rangers (2009), StarCraft strategy (2014), The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt (2019), Death Stranding (2019), shooters Half-Life 2 (2004), Team Fortress 2 (2008) and Deep Rock Galactic (2020), S.T.A.L.K.E.R. 2 (2023), etc.

The emergence of memes featuring portraits of anime girls is significant. The cute cartoon faces and childish, teenage clothes are in stark contrast to the sinister contents of the jar, which the girls enthusiastically hold in their hands, hug and hold close to their hearts. Otherwise, the comic effect of using images of attractive anti-heroes from manga (Dio Brando, Johan Liebert, for example) could be explained. The incongruity between the scale of the atrocity represented and the means by which it is inflicted – that very drink – is illogical.

A jar with krotovukha inside is “given” to media personalities: current and former politicians, TV presenters, bloggers, game designers, athletes and others. It is difficult to draw any clear patterns here; except for one: the heroes of the latest news are the most in demand. For example, after Argentina won the World Cup, the picture of the best player of 2022 – Lionel Messi – kissing the trophy was edited accordingly, with the caption “The secret is revealed”. A number of memes pay tribute to Russian producer B. Alibasov, who mistakenly drank a clog remover that the fabricator named after an agile animal. Users cannot deny themselves the pleasure of using similar words, although the joke on the injured person is ethically highly questionable.

The potential appeal of the sound of the drink’s name discussed in the previous section gives rise to memes with similarly shaped occasionalisms: golosovukha (Russian: голосовуха, a familiar jar with a graph of a sound oscillogram taped to it, used to describe a voice message), craftovukha (Russian: крафтовуха, the product of a craft brewery), Alenkukha (Russian: аленкуха, the photo shows a glass jar through which the wrapper of a popular Russian chocolate bar – Alenka – can be seen), chelovukha (Russian: человуха, a tincture on human beings, presents memes on the theme of the Kuntskammer’s exhibits), as well as reptilukha (Russian: рептилуха), pikachukha (Russian: пикачуха), and squigovukha (Russian: сквиговуха) – jars in which a dinosaur, Pikachu, and a squig are preserved in alcohol.

The simulation of making a drink with toys becomes a challenge: a horse (My Little Pony), a frog (Kermit the Frog), Stitch, and many others are used. Creators benefit from sets of figures made of super-absorbent polymer that grow in water. In 2008, artist Iain Baxter presented his work “Animal Preserve” at Art Basel, in which he placed toys in jars with clean water.

|

Fig. 11. A meme based on footage from Amalrik’s Thumbelina cartoon. Translation: Sorry, but I’m laughing my ass off. / – What’s that? / – My ex |

The children’s theme is always popular. Again, stylistic dissonance is the defining technique. It is clear that Z. Miler’s Krtek is in the lead, with 49 episodes to choose from. However, many Soviet cartoons are in demand for their national colouring. For example, Thumbelina (1964) makes effective use of the image of the hated “ex”. A coveted jar in the hands of a jolly fat man (Junior and Karlson, 1968), pots in front of a teddy bear and a piglet (Winnie-the-Pooh, 1969) cry out for a makeover. Uncle Fyodor digging a huge hole with a shovel in his hand (Three from Prostokvashino, 1978) is identified as a mole hunter. Dr. Livesey (Treasure Island, 1988), whose infectious laugh already arouses suspicion, holds provocatively two voluminous objects (the mole jar replaced both a skull and a bottle of rum).

We have found much fewer Soviet sources of memes, such as a remade poster by V. Govorkov (“Say No to Alcohol”, 1954), a scene from a L. Gaidai film with a prominent wine theme (Kidnapping, Caucasian Style, 1966), and the usual piles of produce from any Soviet citizen’s agricultural storeroom. The main producers of memes are the younger generations. They were introduced to the cartoon heritage of a bygone era, but have little knowledge of the “adult” realities of that time.

The proximity of the New Year holidays made krotovukha memes with winter and New Year themes popular (such as snowdrifts, Christmas baubles, a festive table, a cat with a glass, etc.). One curious response to the alcoblogger’s video was a parody cartoon showing a mole tasting a tincture made on a human being. But the image that was particularly prevalent was the one that was brought to life in Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar (2014). An original technique was used: the “same” jar was not placed next to the famous character, but the filling of the cylindrical vessel was changed, the image of the Einstein-Rosen bridge – the so-called impenetrable wormhole between the universes – was placed “inside” the jar, leaving the background of the original photo. The philosophical depth and multiple interpretations of this juxtaposition have made the photograph with its scientific undertones a bestseller.

Our ancestors believed that the mole could change the usual order of things, connecting the worlds (the underground and the above-ground, the real and the infernal). The mole became a trickster, endowed with the traits of a cultural hero and a renegade8. The duality of perception of the character and the drink made from its body made the recognisable image variable, polyvalent and suitable for multiple transformations. This largely explains its loud success.

|

Figure 12. A meme based on a frame from Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar. Translation: Presenting to you Christopher Nolan’s Krotovukha. Note: The image shows a wormhole, an important element in the movie. The joke is based on a words- play and on the fact that in Russian the synonym for the Einstein-Rosen Bridge is a “mole hole” (literal translation from Russian into English) or a “wormhole”, while in English only the latter term is used. |

Unfortunate as it is, having power over a living being can often make one feel more successful and mighty. The small, vulnerable but indefatigable mole was unlucky: people had long since turned their attention to it, trying to turn it into a panacea for all sorts of ills. Here is what one can hear in a recipe that has gone viral on the Internet:

echoes of the belief in sympathetic magic (wh ere the devourer gains control over the soul of the victim and the desired qualities of the slain creature are transferred to him);

the ritual power of sacrifice as a universal means of renewal (Bayburin, 1993, p. 217);

the original meaning of the rite (intoxication was equated with symbolic death);

possibly, the cosmogonic meaning (the important sacred time of information dissemination – the chaotic space of the last weeks of 2022);

magic of the elixir;

calling upon the wisdom of the ancestors;

national tradition;

national symbols.

The elements came together in an almost alchemical way. Indeed, so is the “magic drink” itself, seen through the prism of culinary triangle created by K. Levi-Strauss as a combination of raw / rotten (in this case fermented) / cooked (distilled), combining the natural and the cultural – surely in the abstract-scientific sense (2013, p. 40).

There is now a lot of research into what makes videos, threads, and memes go viral. The fact that the krotovukha phenomenon became popular in a single country is, in our view, very valuable for analysis. Discussions, comments, media reactions, marketing promotion techniques, all point to the emergence of viral content with maximum engagement.

The pre-holiday of the New Year period played an important role: anticipation of a miracle, ridiculous and sacrilegious as it may sound. The recipe was described as absurd and eerie. Some defined it as the most important drink of the year, others as the quintessence of the Russian chthonic world. Analysing social media content is often a more effective way of gauging public opinion than surveys, questionnaires or tests.

“Alcohol and Drinking Culture”: I. Prokhorova’s conversation with P. Syutkin and E. Tuzmukhamedov (2015, June 17). In The culture of everyday life. Snob. https://snob.ru/selected/entry/93089/?ysclid=lbwh7wxora166088828 (In Russian).

“On the Corruption of Russian Morals” by Prince M. Scherbatov and “The Journey” by A. Radishchev (1983). Eidelman, N.Y. (Com.). Nauka (In Russian).

“Talk to your child if he is looking for a dead mole body in December”. Karelian Ministry of Health speaks out about krotovukha (2022, December 20). In Daily Karelia. https://gubdaily.ru/news/pogovorite-s-rebenkom-esli-on-ishhet-tushku-krota-v-dekabre-minzdrav-karelii-vyskazalsya-o-krotovuxe/ (In Russian).

Aristotle. History of Animals (1996). V. Karpov (Transl.); B. Starostin (Ed.). Publishing Center of RSUH (In Russian).

Balmont, K. D. (1921). Sonnets of the Sun, Honey and Moon. Song of the Worlds. Spamer Publisher (In Russian).

Barthes, R. (2013). Toward a Psychosociology of Contemporary Food Consumption. Food and Culture. C. Counihan & P. Van Esteric (Eds.). Routledge.

Bayburin, A. K. (1993). Ritual in Traditional Culture: structural and Semantic Analysis of Eastern Slavic Rites. Nauka (In Russian).

Bayburin, A. K. & Toporkov, A. L. (1990). At the Origins of Etiquette. Ethnographic Essays. Nauka (In Russian).

Boguslavsky, V. V. (2004). Feast. In Boguslavsky, V. V. Slavic Encyclopaedia. 17th century. Olma-Press, 2004. Vol. 2. p. 150 (In Russian).

Chukhrova, M. G. & Savitzkaja, N. I. (2012). Young People Alcohol Consumption Motivation in Gender Aspect. The World of Science, Culture and Education, 4, 225–228 (In Russian).

Demin, A. K., Demina, I. A., Demin, A. A. & Demina, I. A. (2012). Russia: the Tobacco Case. Investigating Mass Murder. The First Special Independent Investigation into a Socially Dangerous Business in the National Interest: Little Known Facts, Analysis, Recommendations. Russian Public Health Association (In Russian).

Efremova, T. F. (1996). Dictionary of Word Formative Elements of the Russian Language. Editorial Russki Yazik (In Russian).

Galen, C. (1971). On the Usefulness of the Parts of the Body. S. P. Kondratiev (Transl.); V. N. Ternovsky (Ed.). Izdatelstvo Meditsina (In Russian).

Gukovsky, G. A. (1965). Pushkin and the Russian Romantics. Khudozhestvennaya Literatura (In Russian).

Gura, A. V. (1995). The Mole. In Slavic Antiquities: An Ethnolinguistic Dictionary. Vol. 2. (pp. 682–685). International Relations Publishing House (In Russian).

Hamer, M. (2019). The Mystery of The mole hole. How to Catch the Mole, Find the Meaning of Life and Your Place in Nature. Eksmo (In Russian).

Hegel, G. W. F. (1932). Jenenser Realphilosophie Johannes Hoffmeister. Sämtliche Werke, Georg Lasson (Eds.). Bd. 19: I. Stuttgart.

Herzen, A. I. (1955). Collected Works. Vol. VI. Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union (In Russian).

John of Kronstadt (2008). My Life in Christ. Publishing House of Sretensky Monastery (In Russian).

Lenin, V. I. (1962). Collected Works. Vol. 33. State Publisher of Political Literature (In Russian).

Levi-Strauss, C. (2013). Food and Culture. C. Counihan & P. Van Esteric (Eds.). Routledge Publ.

Lovchev, V. V. (2012). Alcohol in Russian Culture (Conflictological Aspect). Scientific Journal “Bulletin of the Technological University” (In Russian).

Marchenko, N. G. (2013). Internet-Meme Like Storage of the Cultural Code of Internet-Community. Kazan Science, 1, 113–115 (In Russian).

Marx, K. & Engels, F. (1957). Collected Works. Vol. 8. State Publisher of Political Literature (In Russian).

Matheson, Richard R. (1985). The Eternal Search: The Story of Man and His Drugs. G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

Matvey Vidro (2023). New krotovukha varieties! [Video file]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/1OIH-5c6lLQ (In Russian).

Naranovich, S. (2021, July 13). The Dark Call of Arcane Mole-Ism: How Moles Were Studied in Antiquity and why it Matters. In The Knife: Intellectual Magazine about Culture and Society. https://knife.media/krotovism/?ysclid=lbuv6hpl17774061306 (In Russian).

Pausanias (1996). Description of Greece S. P. Kondratiev (Transl.); E. V. Nikitiuk (Ed.). Part 2: books 5–10. Aletheia Publishing (In Russian).

Pliny the Elder (1995). Natural History. G. S. Litichevsky (Transl.) In Archives of the History of Science and Technology. Issue 2: Collection of articles, pp. 141–190. Nauka (In Russian).

Sementsov, M. V. (2003). Use of Means and Products of Animal Origin in Folk Medicine of the Kuban Cossacks. In: Results of folklore and ethnographic research of ethnic cultures of the North Caucasus in 2002. Dikarev readings (9): Proc. of the Regional Scientific Conference (pp. 75–90). Kraybibkollektor Press (In Russian).

Shakespeare, W. (1917). The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. D.C. Heath & Co.

Song, J. (2015). Wine in the Socio-Cultural Landscape of Russia and China [PhD thesis, Astrakhan State University]. 006645111 (In Russian).

State Duma legislator threatens imprisonment for krotovukha tasters (2022, December 14). In Business Online: Business E-Newspaper. https://m.business-gazeta.ru/news/576066?ysclid=lbz06kyrmp849958770 (In Russian).

The Closet of the Eminently Learned Sir Kenelme Digbie, Kt., Opened (2001). Sir Kenelme Digbie, Peter Davidson, Jane Stevenson (Eds.). Prospect Books.

Uspensky, B. A. (1996). Selected Works. Vol. I. LRC Publishing House (In Russian).

Vasinkevish, О. & Kukhineva, Z. (2021, March 13). Zdeněk Miler and his Mole who conquered the world. In Radio Prague International. https://ruski.radio.cz/cheshskie-multfilmy-eto-serezno-8710238/3?ysclid=lbwatoct2r285960218 (In Russian).

Yakovlev, A. A. & Babich, N. V. (2015). Moles and Protection against them. Zashchita i karantin rastenii, 2, 34–37 (In Russian).

Yakushenkov, S. N. & Song, Jie (2015). Cultural Security and Factors of Development of National Alimentary Culture. The Caspian Region: Politics, Economics, Culture, 4, 247–253 (In Russian).

Barthes, R. (2013). Toward a Psychosociology of Contemporary Food Consumption. Food and Culture (C. Counihan & P. Van Esterik, Eds.). Routledge.

Digbie, K., Davidson, P., & Stevenson, J. (Eds.). (2001). The Closet of the Eminently Learned Sir Kenelme Digbie, Kt., Opened. Prospect Books.

Hegel, G. W. F. (1932). Jenenser Realphilosophie Johannes Hoffmeister (S. Werke & G. Lasson, Eds.). F. Meiner.

Levi-Strauss, C. (2013). Food and Culture (C. Counihan & P. Van Esteric, Eds.). Routledge.

Matheson, R. R. (1985). The Eternal Search: The Story of Man and His Drugs. G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

Shakespeare. (1917). The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. D.C. Heath & Co.

Matvey Vidro (Director). (2023). Новые сорта Кротовухи! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1OIH-5c6lLQ

Алкоголь и питейная культура: Беседа И. Прохоровой с П. Сюткиным и Э. Тузмухамедовым. (2015). snob.ru. https://snob.ru/selected/entry/93089

Байбурин, А. К. (1993). Ритуал в традиционной культуре: Структурно-семантический анализ восточнославянских обрядов. Наука.

Бальмонт, К. Д. (1921). Сонеты солнца, мёда и луны: Песня миров. С. Ефрон.

Богуславский, В. В. (2004). Пиры. В Славянская энциклопедия. XVII век (Т. 2, с. 150). Олма-пресс.

Васинкевич, О., & Кухинева, З. (2021, март 11). Зденек Милер и его Кротик, который покорил мир. Radio Prague International. https://ruski.radio.cz/cheshskie-multfilmy-eto-serezno-8710238/3

Герцен, А. И. (1955). Собрание сочинений: В 30 томах: Т. VI. АН СССР.

Гуковский, Г. А. (1965). Пушкин и русские романтики. Художественная литература.

Гура, А. В. (1995). Крот. В Славянские древности: Этнолингвистический словарь: В 5 томах (Т. 2, сс. 682–685). Международные отношения.

Дёмин, А. К., Дёмина, И. А., Дёмин, А. А., & Дёмина, И. А. (2012). Россия: Дело табак. Расследование массового убийства. Первое специальное независимое расследование социально опасного бизнеса в национальных интересах: малоизвестные факты, анализ, рекомендации. Российская ассоциация общественного здоровья.

Депутат Госдумы пригрозил тюремными сроками дегустаторам «кротовухи». (2022, декабрь 14). БИЗНЕС Online. https://m.business-gazeta.ru/news/576066

Ефремова, Т. Ф. (1996). Толковый словарь словообразовательных единиц русского языка. Русский язык.

Иоанн Кронштадтский. (2008). Моя жизнь во Христе. Издательство Сретенского монастыря.

Ленин, В. И. (1969). Полное собрание сочинений: В 55 томах: Т. 33. Государство и революция. Государственное издательство политической литературы.

Ловчев, В. М. (2012). Алкоголь в российской культуре (конфликтологический аспект). КНИТУ.

Маркс, К., & Энгельс, Ф. (1957). Избранные работы (Т. 8). Государственное издательство политической литературы.

Марченко, Н. Г. (2013). Интернет-мем как хранилище культурных кодов сетевого сообщества. Казанская наука, 1, 113–115.

Наранович, С. (2021, июль 19). Тёмный зов потаённого кротовизма: Как изучали кротов в Античности и почему это важно. Нож: интеллектуальный журнал о культуре и обществе. https://knife.media/krotovism/

Павсаний. (1996). Описание Эллады: В 2 частях: Т. Часть 2: Книги 5–10 (Э. Д. Фролов, Ред.; С. П. Кондратьев, Пер.). Алетейя.

Плиний Старший. (1995). Естественная история. В Г. С. Литичевский (Пер.), Архив истории науки и техники. Выпуск 1: Сборник статей (сс. 141–190). Наука.

«Поговорите с ребенком, если он ищет тушку крота в декабре». Минздрав Карелии высказался о «кротовухе». (2022, декабрь 20). Daily Карелия. https://gubdaily.ru/news/pogovorite-s-rebenkom-esli-on-ishhet-tushku-krota-v-dekabre-minzdrav-karelii-vyskazalsya-o-krotovuxe/

Семенцов, М. В. (2003). Использование средств и продуктов животного происхождения в народной медицине кубанских казаков. В Итоги фольклорно-этнографических исследований этнических культур Северного Кавказа за 2002 год. Дикаревские чтения (9): Материалы Региональной науч. Конф., Краснодар, 10–13 окт. 2003 г. (сс. 75–90). Крайбибколлектор.

Старостин, Б. А. (Ред.). (1996). Аристотель. История животных (В. П. Карпов, Пер.). Издательский центр Российского гососударственного гуманитарного университета.

Сун, Ц. (2015). Вино в социокультурном ландшафте России и Китая [PhD Dissertation]. Астраханский государственный университет.

Успенский, Б. А. (1996). Избранные труды. Том I. Семиотика истории. Семиотика культуры. Языки русской культуры.

Хамер, М. (2019). Тайна кротовой норы. Как поймать крота, найти смысл жизни и своё место в природе. Эксмо.

Чухрова, М. Г., & Савицкая, Н. И. (2012). Мотивации потребления алкоголя молодежью в гендерном аспекте. Мир науки, культуры, образования, 4, 225–228.

Эйдельман, Н. Я. (Ред.). (1983). «О повреждении нравов в России» князя М. Щербатова и «Путешествие» А. Радищева: Факс. Изд. Наука.

Яковлев, А. А., & Бабич, Н. В. (2015). Кроты и защита от них. Защита и карантин растений, 2, 34‑37.

Якушенков, С. Н., & Сун, Ц. (2015). Культурная безопасность и факторы развития национальной алиментарной культуры. Каспийский регион: политика, экономика, культура, 4, 247–253.

__________

1In a mythological context, the upside-down position is seen as non-random, as in a recent recipe. Reverse, “upside down” behaviour is essential for contact with representatives of the other world (Uspensky, 1996, p. 460).

2In L. Amalrik’s popular Soviet cartoon, the image is heavily altered for ideological reasons; D. Bluth’s animation is closer to the original in this sense.

3In 2001, the German book titled Vom kleinen Maulwurf, der wissen wollte, wer ihm auf den Kopf gemacht hat (English: The Story of the Little Mole Who Knew This Was None of his Business) was translated into English, and in 2014 into Russian.

4In 1977, the Japanese writer Tarō Gomi published an informative book on the same subject, but without the mole character acting. And the subject matter, especially in prose, does not lend itself to global conclusions about genre innovation.

5A play on words describing the mole tincture expert, based on the similarity to the word “sommelier”, Russian: кротовье, romanized: krotovʹe.

6This is an analogy with the feast as an ancient form of interaction between the living and the dead, as well as with the tradition of the Russian bratchina, a communal Slavic feast.

7In one of the January videos based on the trend, the vocabulary is not organised according to uniform linguistic rules, but the choice of words is symptomatic: кротовуха (romanized: krotovukha), муха (a fly), степуха (romanized: stepukha, a colloquialism meaning scholarship), бицуха (romanized: bitsukha, a colloquialism meaning biceps), порнуха (romanized: pornukha, a colloquialism meaning a porn film) (Vidro, 2023).

8We would like to thank Professor Sergei Yakushenkov for a number of valuable comments that helped to construct the hypothesis of the study, in particular for suggesting the term “tricksterism”, which succinctly conveys the nature of the phenomenon