Table of Content | Содержание

Children’s Victimization in Turkish Cinema between the 1970s and the 1980s: A Political Economy Perspective

Menderes Akdağ (a), Serhat Yetimova (b) & Hatice Yaren Eser (c)

(a) Adnan Menderes University. Aydın, Turkey. Email: menderes.akdag[at]adu.edu.tr

(b) Sakarya University. Serdivan, Turkey. Email: serhaty[at]sakarya.edu.tr

(c) Independent Researcher. Turkey. Email: yareneser21[at]gmail.com

Received: 11 June 2022 | Revised: 30 September 2022 | Accepted: 11 October 2022

Abstract

Between the 1970s and 1980s in Turkey, there were various problems such as rapid urbanization, migration fr om village to city, economical problems such as embargo and neoliberalism and political violence over the military coups. Our study focuses on the problems experienced by children which lead to child victimization through Turkish movies. In our research, we used deduction and induction methods together. Based on the political and economic developments in the period between 1970 and 1980, we looked at how these dynamics were reflected in the films by thematic analyze method. Here are the themes that we found in the films which are commonly used in relation to children in cities and their urbanization, child marriage, smuggling, political violence and education. In conclusion of the Turkish press and movies and according to the interviews we did with the people who witnessed those periods, the problems related to children manifest themselves quite heavily and negatively. The Turkish society, which is experiencing a rapid urbanization process, has continued the patriarchal, sexist, religious-conservative and statist discourse they brought fr om the feudal village life in modern cities as well. While this is a problem that the press and cinema criticize with a common approach, it is seen that children are also a part of this process.

Keywords

Turkish Cinema; Children in Films; Turkish Cinema History; Children; Media; Thematic Analyze Method

Детская виктимизация в турецком кино 1970‑х и 1980-х годов: политико‑экономическая перспектива

Акдаг Мендерес (a), Йетимова Серхат (b), Эсер Хатидже Ярен (c)

(a) Университет Айдына Аднана Мендереса. Айдын, Турция. Email: menderes.akdag[at]adu.edu.tr

(b) Университет Сакарья. Сердиван, Турция. Email: serhaty[at]sakarya.edu.tr

(c) Независимый исследователь. Турция. Email: yareneser21[at]gmail.com

Рукопись получена: 11 июня 2022 | Пересмотрена: 30 сентября 2022 | Принята: 11 октября 2022

Аннотация

Между 1970-ми и 1980-ми годами в Турции существовали различные трудности, такие как быстрая урбанизация, миграция из деревни в город, экономические проблемы, такие как эмбарго и неолиберализм, а также политическое насилие, связанное с военными переворотами. Наше исследование сосредоточено на проблемах, с которыми сталкиваются дети и которые приводят к виктимизации детей при посредстве турецких фильмов. В нашей работе использованы методы индукции и дедукции вместе. Основываясь на политических и экономических событиях в период между 1970 и 1980 годами, мы рассмотрели, как их динамика отразилась в фильмах, пользуясь методом тематического анализа. Перечислим темы, обычно используемые в отношении детей в городах, которые мы нашли в фильмах: их урбанизация, детские браки, контрабанда, политическое насилие, образование. По заключениям турецкой прессы и фильмов, а также, судя по интервью, которые мы брали у людей, бывших свидетелями тех периодов, проблемы, связанные с детьми, проявляются очень ощутимо и негативно. Турецкое общество, переживающее стремительный процесс урбанизации, продолжило патриархальный, сексистский, религиозно-консервативный и государственнический дискурс, который оно принесло из феодальной деревенской жизни в современные города. Хотя это проблема, которую пресса и кино в целом критикуют, заметно, что дети также являются частью этого процесса.

Ключевые слова

турецкое кино; дети в кино; история турецкого кино; дети; СМИ; метод тематического анализа

Introduction

It is seen that the neoliberal policies went bankrupt in the Great Depression in 1929. But neoliberal policies became an important reason for the Republic of Turkey to adopt a state-led modernization movement after the 1980s. In 1931, the principle of statism entered the program of the Republican Party. In this process, the First Industrial Plan was implemented in 1933, taking the model of the Soviet Union as an example. The factories symbolized of modern Turkey that continued until the 1980s, Turkey adopted the mixed economic model and took steps to rapidly catch up with the modern world. This economic-political approach continues until the 1980s. But with the military interventions in 1960, 1971, and 1980, Turkey transitioned to liberal and then to neoliberal economics. So, privatization and liberalization increased. Since the 1980s, Turkey prefers the transition from an industrialized production-based model to a consumption-based liberal economy model in the fields of tourism, real estate/residence/land and media. All public gains are privatized and disposed of which deeply shakes the reputation of the factories (Bila 2020).

After the 1980’s coup d’etat “Liberalization was not accompanied by stabilization. Especially after 1987 and during much of the 1990s, Turkey suffered high inflation rates, high real interest rates, high budget deficits, and rapidly accumulating public debt” (İzak Atiyas & Ozan Bakis (2015, p. 1).

Looking at the sectors according to Gross National Product (GNP) on the basis of the five-year development plans implemented in Turkey, it is seen that the service sector grew well from 1968 to 1980, and the industrial sector gained momentum, but the share of the agricultural sector in GNP decreased. This indicates that the peasantry and agricolation have begun to disappear and that it has been replaced by urbanism (Kazgan, 2014). Thus, cities become chaotic spaces.

Since the 1970s according to statistics of UNIDO data set INDTSAT2, as İzak Atiyas & Ozan Bakis (2015) indicates traditional industries such as food and beverages, tobacco, and textiles have declined over time. By contrast, the shares of nonmetallic mineral products, machinery and equipment, and motor vehicles have increased.

Despite the population increase until the 1970s, Turkey’s resources were somehow self-sufficient. Remittances sent to Turkey by Turkish workers who were working abroad also play an important role in closing Turkey’s foreign trade deficit. In addition, in that period the Soviet Union (USSR) was an important oil and gold producer. In order not to strengthen the USSR, gold and oil prices were kept constant for a long time. However, this system collapsed in the 1970s. Oil prices have increased eightfold. Turkey was caught unprepared for the world oil crisis and therefore, monetary policies were devalued in Turkey. With the increase in imports, Turkey’s foreign debt increased and also inflation started to rise in Turkey (Yeni Asır, 1978, July 15); justice in the distribution of income has deteriorated. All these have led to the spread of poverty in Turkey (Kazgan, 2014).

The development of Turkish cinema cannot be separated from the political and economic development mentioned here. The current liberal and neoliberal economic issues have affected the rise, contents, and artistic and cultural nature of Turkish cinema. Interpreting the representations of children in Turkish films on this axis brings an innovative perspective to Turkish cinema.

The main character of Turkish cinema between 1960 and 1980 is melodrama (Pehlivan, 2007, p.22) As Abisel claims, “These films mostly targeted the female audience from the middle class and the community from the shanty towns which was gradually getting crowded (...) Abisel discusses the function of the family as an agent that legitimizes and normalizes authoritative and patriarchal ideologies. The story in popular films takes place mostly in the atmosphere indoors, around family and small groups like it. Family, as the dynamic of the current social structure, is a very suitable tool for legitimizing and reproducing the given hegemonic ideologies in its small atmosphere” (Abisel 2005, as cited in Pehlivan 2007, p. 25).

In films before 1980, it is seen that family films deal with women and solidarity as a theme. Films such as Bizim Aile (1975) and Aile Şerefi (1976) are good examples in this sense. In the films shot in the post-2000 period, it is emphasized that consumption, conflict, individualization and popular visual culture are dominant. In the films shot after 2000, children were also involved in problems such as materialistic self-interest, loneliness, and loss of parental control. For example, unlike the pre-1980 period in the movie scenes of Babam ve Oğlum (2005) and Dedemin İnsanları (2011), it is clear that the uniting and keeping function of the family disappeared, the institution of ‘family’ was ignored, and children, as captives of popular culture, tended towards an extreme, unlimited and irresponsible consumption culture. On the basis of all these social problems, the conditioning effect of the liberal market economy is seen.

According to Emre (2007, p.105-106) who analyzes Ayşecik films in his thesis, Ayşecik character as a star-child character symbolizes the Turkish society, which emulates Western culture, stuck between East and West, trying to westernize, in other words, modernize. The economic and political indicators of the poverty and deprivation representations in the films are related to the Westernization/modernization process.

Examining the theme of childhood in Arabesque films, Elal (2013, p. 375-376) also sees the deprivation, oppression, exclusion and complexes experienced by children in such films as a reflection of the problem of Westernization. According to Elal (2013), modernization in Turkish society was perceived as Westernization with a wrong method. This has increased the sense of lack in the society. As a matter of fact, the problems in the films in which children stand out as stars are also a part of Turkey’s lack of modernization (underdevelopment-backwardness, etc.). For this reason, the childlike moods of Turkish society show themselves in the films of the 1960s and 1970s.

Examining the children’s films of the period through Ayşecik films, Doğan (2019, p. 322) states that the child characters in these films do not reflect real-life children; they are heroes and act like adults. These children come to the fore as idealized heroes instead of being real characters. As the most important reason for this situation, Doğan (2019) sees the function of cinema as an entertainment and consumption tool.

Methods

Considering the contemporary approaches of French cultural philosophers Paul Ricoeur, Antoine de Baecque, Christian Delage and Edhem Eldem, who determined the methodology and epistemology of contemporary historiography, document historiography is not sufficient to understand the spirit and culture of the period. It is also very important to question by whom and for what purpose the documents are written. Documents can also be biased. Scepticism and a critical attitude in this direction will open the door to asking different questions and evaluating the problems in a multifaceted way. Along with the documents, the conditions of the period should be evaluated together. In this respect, historical epistemology provides a method that operates the principles of research, explanation and interpretation. This perspective should also be adapted to the history of cinema (Yıldırım, 2015, p. 41-42).

In our research, we benefited not only from filmography. In addition to this, we also scrutinized the news reflected in the press along with mainstream or critical film samples and written and oral history literature together. We also evaluated the oral history interviews by referring to the testimonies living in the period. In summary, we tried to obtain a comprehensive view of the period.

According to Akar (2020, p. 283-284) who argues that the history of Turkish cinema should be written with a new perspective and method, Turkish cinema should be rewritten and evaluated with an analytical, not a chronological, point of view. This approach, which should be handled at the micro level, thematically and analytically, will make the perspective on Turkish cinema more in-depth and original. When choosing our theme we try to give answers to the following questions. Our research question is how were the children affected by neo-liberal politics and what kind of abuse were the children exposed to in the face of the economic problems of the period?

Method

We used the method of thematic analysis in our research. In the films in which children were represented, we determined and analyzed themes according to the event, phenomenon, situation and object that children have been associated with. We determined the stages of familiarization, coding, generating themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and writing up which are frequently used in the thematic analysis method in relation to the representations of children in films. (Kiger and Varpio, 2020; Caulfield, 2019). We tried to understand how economic-political developments affect children represented in Turkish films between the years 1970-1980.

Sample

In our research, 48 mainstream and alternative films released between 1970 and 1980 were analyzed in the context of the child main theme. Besides historical studies, newspapers archive of Hürriyet, Milliyet, Cumhuriyet and Yeniasır, which were among the mainstream newspapers of that period, were simultaneously scanned in the context of news with a child theme.

Coding scheme

In our research, we used deduction and induction methods together. Based on the political and economic developments in the period between 1970 and 1980, we looked at how these were reflected in the films. Here are the themes that we found in the films which are commonly used in relation to children: Urbanization, Child Marriage, Smuggling, Political Violence and Education.

Analysis

The films were examined according to the thematic categories mentioned above, and the events, facts, dialogues and symbols that fit these themes were analyzed in a way that explained the economic-political developments.

Results

Urbanization Problems in the Cities

In the 1970s, traffic accident rates and deaths increased due to the lack of traffic culture. When we look at the newspapers of that period, the reasons such as the increase in vehicle density on the roads in the cities, low traffic standards, and lack of traffic education were effective at the time. Technical and durability problems of vehicles under the trademarks of Murat and Anadol were also a problem. (Hürriyet, 1977, March 24). In this respect, there would be an increase in the number of orphaned children in society.

Traffic problems arise in the cities (Hamsici, 2018). It is seen that vehicles hitting pedestrians sometimes leave the victims they hit in the middle of the road and flee (Hürriyet, 1977, March 21; Hürriyet, 1971, January 2). Many people do not know how to give first aid. In a frogmarching way, the injured people are tried to be brought to the hospital by cars (E.C. Akdağ, personal communication, March 3, 2020). As the roads are filled with cars, children’s safe playgrounds are reduced (Duru, 1970; Erksan, 1971).

|

Picture 1. The person in the role of the peddler, played by Kemal Sunal, expressed his desire for Murat 124 by writing Murat on his three wheeler car. (Seden, 1978). |

|

|

Picture 2. There are no safe playgrounds. Children are playing in the streets (Duru, Driver Nebahat, 1970) and Children die in traffic accidents (Hürriyet, 1977, March 17). |

With the increasing number of cars, children’s interest in cars increases, especially in rural areas. Many children saw cars as part of their play. They ran after cars. Since most families were at work, children were left uncontrolled on the streets. This situation was reflected in the movie of Friend (Güney, 1974). Again, in open-top cars, people used to travel like fish hoards (Gören, 1974). It is known that in those days, many children fell from the car and had an accident, and as a result of these accidents, some children lost their lives and some children became disabled (Y. Akdağ, personal communication, August 31, 2021).

|

Picture 3. Children running after the car (Yılmaz, 1984). |

|

|

Picture 4. The reflection of the children running behind the cars in the rear view mirror in the movie (Güney, 1974) and journey on the car ladder and ceiling (Güney, 1971) |

|

Picture 5. Transporting people in the form of a stack of fish in a truck bed (Gören, 1974) |

Child Marriage

It can be said that child marriage was one of the issues that were frequently reflected in Turkish cinema during the 1970s. Child marriages were extensive before the 1980s. An individual under the age of 18 is a child according to the laws in Turkey. Even with children’s consent, this situation indicates abuse. In the first years of the Turkish Republic, compulsory and co-education practice starts. However, the state staff did not react to child marriages for a long time due to the inability to expand schooling and cultural factors. After World War II, the fact that the school records of 14-year-old girls were deleted because they got married is reflected in the primary school student registers many times (Erbeyli, 1933-1953).

In the 1970s, the migration from the village to the city and the fact that the cities were chaotic places must have frightened the families. Due to cultural factors such as the matter of honour and the reality of poverty, girls were married off to men who were much older than them (Duru, 1965).

|

Picture 6. Old man, child bride scene, (Duru, 1965). |

It was stated during interviews that families used violence against girls who did not want to get married. Emine Cerit Akdağ (personal communication, March 3, 2020) says that in 1950, when she was just 14 years old, she was asked to be married by her father, but when she refused to accept this offer, her father did beat her with tongs. Shortly after this event, Cerit was married to someone older than her. Similar memories were also reflected in Turkish cinema. For instance, in the movie Satılmış Adam/Sold Man, the father of the girl hires a hitman to murder her girl who ran away to marry her husband (Jöntürk, 1977; Hürriyet, 1977, December 25).

Child marriages in the 1970s have a serious impact on Turkish cinema as we see in the films Bride/Gelin, Wedding/Düğün and Diet/Diyet, known as Ömer Lütfi Akad’s trilogy which emphasizes male domination and religious and cultural taboos in Turkish society. For instance, when the father of the house, stuck in money, wanted his younger daughter to marry an older man for a bride price, the elder daughter objected to this. Thereupon, it is seen that the brothers injured the elder sister with a knife (Akad, Wedding, 1973).

|

Picture 7. The girl child who does not accept marriage is subjected to violence by her father (Gören, 1974). |

|

|

Picture 8. In the wedding movie, the elder sister opposes her sister’s marriage because the girl is not yet of age. But her brothers stab the elder sister. Then, the elder sister throws the bride’s veil in the face of her brothers (Akad, Wedding, 1973). |

Director Akad uses the Prophet Joseph’s episode in the Holly Quran which criticizes the patriarchal social culture with metaphors of corpses of siblings, selling of children, bird meat and wedding. In this sense, the director tries to expose moral contradictions. These people represented in the film are seemingly conservative, devoted to their religion and customs. Honour is more important to them than anything else. But honour only tells about the loyalty of women to men. How women will live in their lives, wh ere they will stay, and who they will marry is determined by men. Honour is perceived as a matter of keeping men’s word. Women and children are not asked what they think or want. Even if it is asked, it has no political or economic value. In the film, honour in the language of the landlords is not equivalent to loyalty to the holy book, human values, personal rights and freedoms, but to the fantasies of men. Thus fantasy also attempts to open up a relatively large economic space for men. Women and children are reduced to an economic value by being commodified with their existence in this male-dominated sociality. Akad develops cinematography that shows these contradictions with his camera. The light of his camera brings to light the Turkish sociality of the 1970s.

Sometimes men abuse women and girls on the streets of the cities. According to the news of Yeni Asır newspaper, it is understood that this includes young people as well. A 14-year-old girl in Izmir, while trying to avoid the men’s talk, is hit by a train (Yeni Asır, 1978, June, 20). Harassment in the form of insulting women and following them on the street is also reflected in some films (Refiğ, 1969).

In the 1970 movie Yumurcak Köprüaltı Çocuğu (A child who is a gam-in boy), the character of 7-8 years old boy called Sezercik has a male puppy. Sezercik takes his dog for a walk. A girl of the same age passes through her place with a female puppy. It is quite interesting that Sezercik followed the girl with his dog, saying “a gajo fell on both you and me” to his dog (İnanoğlu 1970). Thus, some harassments of the innocence of children are justified by cinema.

The period between 1960-75 in the history of Turkish cinema is the commercial-popular period. There are child stars in movies. Agitating melodramas are reconstructed in a child-centered manner. In films such as Ayşecik and Yumurcak, children are heroes. Children who are heroes are portrayed as people who “catch/capture the thugs, reconcile their mothers/fathers, and defeat the wicked”. Movies like Canım Kardeşim (1973) rarely break this mold and tell the reality of poverty through the eyes of an orphaned antihero child. A child whose only dream is to have a television, passes away before he can find the money to treat his cancer. (Becerikli, 2018, pp.341-343) This shows that the health system has begun to commercialize. A similar approach is also used in Ömer Lütfi Akad’s Bride. Unable to find the money to have her child treated, the mother watches helplessly as her child dies.

In the period between 1970 and 1980, the news that boys were also abused appeared in the press (Yeni Asır, 1978, June 28). In the movie İnsanları Seveceksin/You will love people, prison conditions were described as very bad. It is shown in the movie that the inmates abuse some boys in the children’s ward to gain money (Gülgen, 1979).

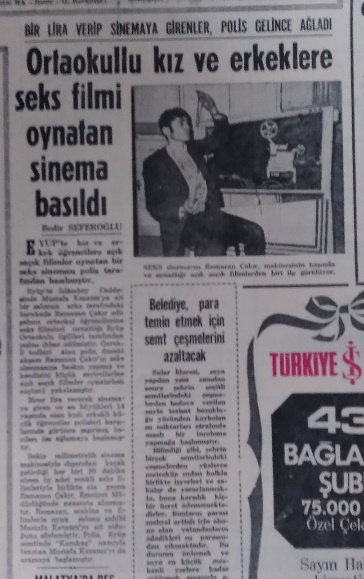

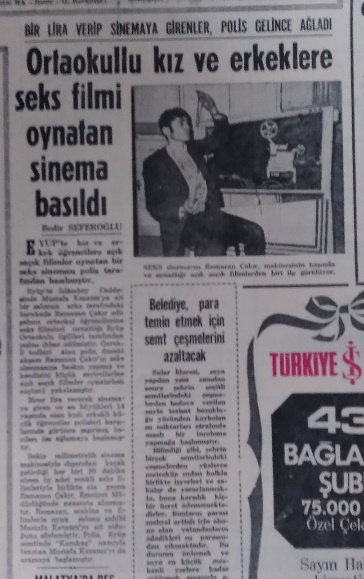

It is seen that in those days, eroticism began to be instilled into society through the press, magazines and cinema. This situation can be considered as one of the reasons for the increase in abuse cases. Moreover, children are also affected by the erotic film frenzy that started in cinemas. It is seen in the press that some filmmakers did allow children to watch such films in the greed of making money.

|

|

Picture 9. Abuse news reflected in the press (Yeni Asır, 1978, June 28) and (Hürriyet, 1971, January 19). |

It can be thought that social disintegration, the fraction of the family, and the change in understanding among young people did increase intra-familial conflict. Suicide incidents also increased in that period (Orbey, 1975). The increase in migration from the village to the city, the erosion of cultural values, poverty, and the marketing of being a singer and movie star as hope in society increased the cases of running away from home during the 1970s. In those days, the cases of missing girls were on the news (Hürriyet, 1977, January 9; Yılmaz, 1966). There were reports that some girls who did run away from home were abused (Hürriyet, 1977, January 9).

Smuggling

It is seen that children were used in the sale of illegal cigarettes and alcohol during the 1970s and 1980s. Since the mid-1960s, when drug use increased in the West, America in particular claimed that Turkey was the source of this problem. The US asked the Turkish government to ban poppy cultivation. The Turkish government resisted this situation. Nihat Erim’s government was established on 26 March 1971, instead of Süleyman Demirel’s government, which resigned after the 12 March 1971 Memorandum, and on 29 June 1971 the cultivation of poppy was banned (Cumhuriyet, 1971, June 30).

In the 1970s, Turkey provided 55% of the world’s poppy production, which was used to produce morphine for medicinal purposes. Western companies began to produce poppies in India. The United States started poppy cultivation in Arizona. Despite this, when the MSP (Conservative Party)-CHP (Republican Party) coalition government lifted the ban on the cultivation of poppies on Turkish peasants on July 1, 1974, the US again started to accuse Turkey of being the centre of drug trafficking (Başlamışlı, 2021).

However, there were also developments in Turkey that will justify the thesis of the USA. In 1972, Turkish senator Arif Kudret Bayhan was caught in France with 146 bases of morphine (Milliyet, 1972, March 10). In a short time, Bayhan’s senatorship was cancelled with a vote in the Assembly. This would mean Turkey’s official admission of the senator’s crime. The trials ended in 1973. Bayhan was sentenced to fifteen years in prison by the French judiciary.

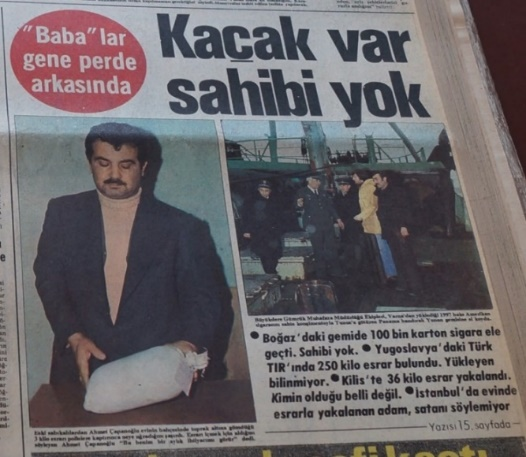

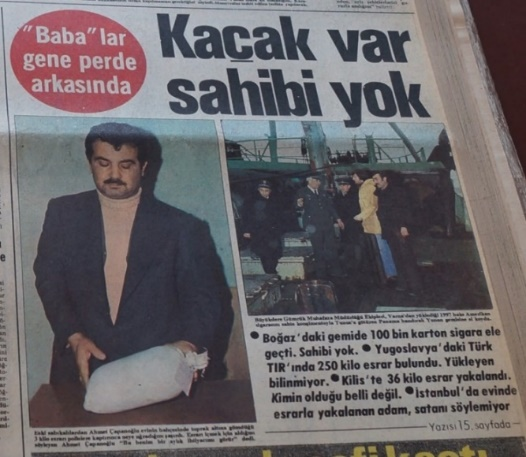

Even in 1977, news appeared in the newspapers that the issue could not be fully clarified (Hürriyet, 1977, March 27). In those years, not only drugs but also illegal cigarettes and alcohol incidents were seen. In the Bosphorus, 100 thousand cartons of smuggled cigarettes were seized on a ship, 250 kilos of hashish in Yugoslavia on a Turkish truck going to Europe, and a large number of drugs in different parts of the country. It is known that these contraband cigarettes were secretly sold on the roads (Hürriyet, 1977, March 18).

There were also allegations that some children have fallen into the hands of smugglers and drug dealers. In the movie Meryem ve Oğulları, the story of a mother trying to save her child who fell into the hands of a drug and smuggling gang from an early age is screened (Seden, 1977).

It is known that not only cigarettes brought illegally from abroad, but also state-owned TEKEL (Monopoly) products, which couldn’t be found in the market due to hoarding and stockpiling were illegally sold on the streets and in shops. This situation is reflected in the movies of İstanbul 79 (Aksoy, 1979) and Çöpçüler Kıralı/ King of the Scavengers (Ökten, 1977).

The UN declares 1979 the World Year of the Children (Unicef, 2021; Hürriyet, 1977, March 17). Despite this, it is known that children are often used in the sale of smuggled cigarettes on the streets. This situation is also reflected in the movie of Taşı Toprağı Altın Şehir/The Golden City. (Aksoy, 1978).

|

|

Picture 10. Smuggling news in newspapers (Hürriyet, 1977, March 18) and Representation of a boy trying to sell illegal cigarettes on the street in the movie Taşı Toprağı Altın Şehir (Aksoy, 1978). |

In the 1970s, some families had their children work as shoe shiners. Children would try to sell ready-made food products such as bagels in crowded streets and alleys. It was seen that some children were employed in heavy labour in industrial areas, exceeding the master-apprentice relationship. Some children were even begged by their families. In addition to this, gangs sprang up that made some orphan children work in problematic ways and sometimes made them beg. The situation of poverty (Ankara, 2012) was also reflected in the films of Sezercik and Ayşecik, whose sequels were shot throughout the 1970s (Göreç, Öksüzler, 1973). In this sense, it is interesting that the movie Keşanlı Ali Destanı begins with the image of children trying to collect money by playing instruments on the street (Yılmaz, 1964). It can be said that the period of 1970-1980 was an unfortunate period in terms of child victimization.

Political Violence

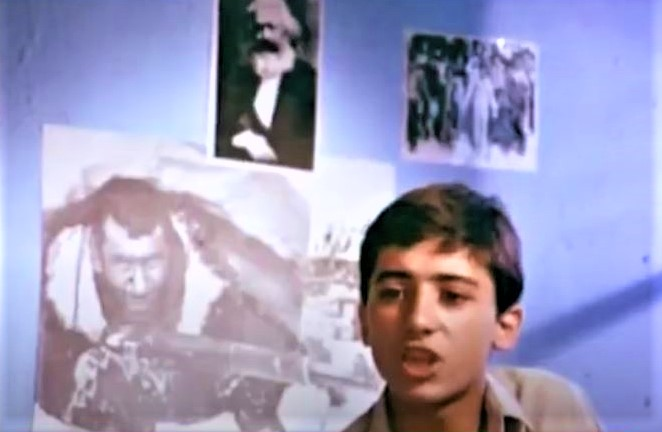

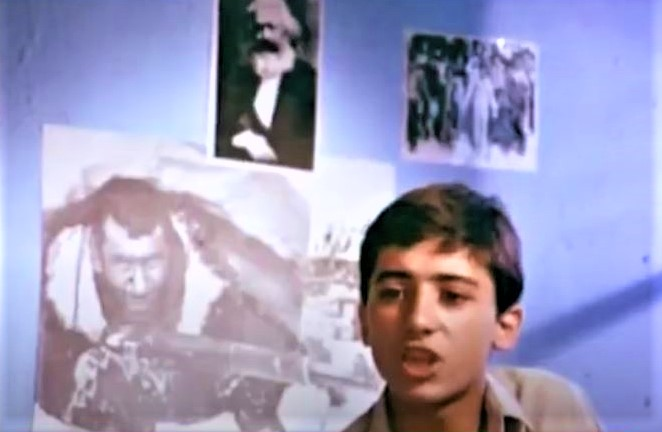

Shooting at a high school in Çorum (a calm city) reflects how much violence has spread to Anatolian cities, and violence increasingly was including children (Hürriyet, 1977, March 23). It is seen that even children at the secondary school level were seriously affected by ideologies (Ökten, 1974). It can be stated that children were mostly used by political organizations for similar purposes to distribute leaflets (Yeni Asır, 1978, July 26). It is seen that some of the children were caught between two fires and lost their lives (Yeni Asır, 1978, June 16). In addition to all these, shooting into the air and being killed by accidental bullets at weddings have been the subject of many tombstones and films (Güney, 1968). This situation also indicates the importance of individual armament in terms of the economy.

|

Picture 11. Photos of Karl Marx and Yılmaz Güney in the background of an adolescent boy trying to convince his family about socialism and communism in a movie (Ökten, 1974). |

The film Yusuf and Kenan (1979), written and directed by Ömer Kavur, also contains political references to Turkey in the 1970s. Their father was killed in the village due to a blood feud, and the children became orphans. They changed their way to Istanbul. As to Istanbul, it was like a big village, ruined and rundown. The main problem in the city was money and livelihood. Children had to live unemployed and without money. They could not get help from anyone. After that, they met with street children. Once, Yusuf saves the life of the gang leader and can get right to join the gang team. Kenan is not taken into the gang because he is younger. But, Kenan gets lucky and can get a job at an auto-mechanic service and works legally.

On the other hand, Yusuf tries to earn money by stealing auto tapes. He tries to win the favour of the gang leader. He gives them to the gang leader to sell the tapes he stole and gets his commission. But after a while, they are caught by the police. The gang leader, who escaped from the police thanks to his nationalist friends, says that he is dedicated to the “holy cause” and thus avoids being imprisoned. But Yusuf is arrested and sent to prison. Yusuf is trying to live under difficult conditions in prison. These developments in the film emphasize the subjective and widespread political character of both the social life and the justice system in Turkey in the 1970s, and the economy appears to be the fundamental problem for any age.

Education

Until the Democratic Party governance, it was the peasants’ responsibility to build schools in the villages. However, many villages could not cope with it. The Ministry of National Education (MEB) and special provincial administrations started to undertake the construction of village schools since the DP government (Akdağ, 2020).

However, sufficient funds could not be allocated from the national budget to build schools in the villages. This situation caused the physical and social facilities of village schools to remain in poor condition for many years. On the other hand, the villagers had to meet many of the needs of the schools, such as coal. Coal aid to village schools was made possible for the first time by the Ministry of National Education in 1993, during Minister Köksal Toptan’s governance (Toptan & Hacıoğlu, 2017, p. 194-195).

For many years, the construction, maintenance and repair of village roads and bridges, water supply to the villages and payment of the salaries of imams and guards were left to the village legal entities. Village budgets were often not strong enough to cover all of them. For this reason, village streets were usually muddy or dusty. Children used to go to school in difficult conditions which were widespread throughout Turkey from east to west (M. Sertel, personal communication, January 17, 2018).

The basic needs of the village schools and the students were tried to be covered by the voluntary aid of citizens. In the movie Hababam Sınıfı Uyanıyor/ Hababam Class Awakens (Eğilmez, 1976), the aid of Istanbul Private Çamlıca High School’s students to bring construction materials to a village school in Anatolia makes them twin.

Overcrowded classrooms were a serious problem in cities of Turkey. So, more teachers were needed. But, the government met the demands of teachers in temporary positions. According to the news of Hürriyet newspaper, these teachers have requested to be recruited permanently. It is claimed that efficiency in education and training did decrease because this problem couldn’t be resolved (Hürriyet, 1977, July 24). At the same time, teacher training policies were not seriously evaluated by the Turkish state. It is said that some teachers were trained in an unqualified way (A. Konaklı, personal communication, June 17, 2018). As a matter of fact, according to Kaçmaz (2020, p.154) who analyzed the films of the Hababam Class, the source of the problems in the education system is the indifference of the authorities and parents, not students.

|

|

Picture 12. Hababam Class students bring materials with trucks to build a new school in the village (Eğilmez, 1976). |

On the other hand, electricity began to be brought to the villages in the mid-1970s. In cities, problems arise in supplying electricity to slums. In the 1970s, there were also continuous power cuts. The phrase “the electricity was cut off, so I couldn’t do my homework”, which was often heard from students at that time, emerges from a reality. The gas lamp continues to exist for a while. On the other hand, this situation of children living in one-room houses affects their success in school (Gülgen, 1979).

Children living in slums who can’t go to school are shown in the movie Yarınsız Adam/Man without Tomorrow. In the film, graffiti, which was common in those years, draws attention. With this scene depicting graffiti, the director wants to show that there is an inequality of opportunity in education and that the quality of education is not good. The opening scene of the movie begins with a crowded chaotic classroom environment (Jöntürk, 1976).

Turgut Demirağ, who studied cinema in the United States, focuses on the conflict between traditional and modern religious education in his movie titled Aynı Yolun Yolcusu/ Traveler of the Same Road (1973). He criticizes the soul-destroying, autocratic education system in Turkey with all its cultural, religious and social dimensions. According to Demirağ, the only way to protect children from the restrictive aspects of this system is to provide them with an analytical and project-based education wh ere they can eventually gain professional skills. In addition, it is seen that children do not develop without the social, cultural and artistic knowledge and skills conveyed to children by Sadri Alışık as a famous hero.

Discussion

After the Second World War, Turkey moved away from agricultural production with the financial support of the United States. With a rapid urbanization process, Turkish society has been reduced to a consumer position. Cities are overflowing with cars and residences. This situation negatively affected the social lives and playgrounds of the children.

With rapid urbanization, families and their children have been deprived of quality education opportunities. Families whose profession, job and economic earnings were not sufficient forced their children to marry at an early age. On the other hand, children were involved in jobs such as singing and smuggling to continue their education and to contribute to the family budget. Although these situations are handled with their ridiculous aspects in mainstream cinema, they have been the subject of criticism in social realist cinema examples. The patriarchal, male-dominated, sexist (seeing women and children as worthless) and strict Islamic conservative aspects of Turkish society have been criticized.

The economic and political developments experienced by Turkey also explain the problems experienced by children in Turkish cinema. Turkey’s transition to a neoliberal consumption economy after World War II weakened the social aspect of the state. This situation, along with rapid urbanization, has caused problems in areas such as need for shelter, education, employment, nutrition and socialization.

The political and economic instability experienced between the years of 1970‑1980 and in further times, the collapse of state authority, the high inflation, the uncontrolled migration from village to the city caused to increase of chaotic environment in the cities and they affected children negatively. This situation is reflected in the press and cinema of the period in a similar way. As far as we can follow from the press and movies and according to the interviews with the people who witnessed the period, the problems related to children reveal that they are adversely affected and live in very difficult living conditions.

Apart from those who were deprived of the right to education, there were also those who were severely abused. They had difficulty in accessing basic food. Only, a few Turkish movies with realistic features reflect these children’s problems. Turkish cinema does not bring serious proposals and answers to the problems occurred in the meantime most of the films agitate about the current situation in order to attract more people to the movie theatres. This situation can also be explained as the commercialization of cinema depending on neoliberal policies.

Nevertheless, some of the socialist/Marxist and realist directors1 implemented a critical attitude against the mainstream influence of melodramatic Yeşilçam cinema in 1970s, although their number was not so many.

The mentioned directors took a close look at the cultural and educational processes in Anatolian cities in order to understand and get to the root of the problems experienced by children in modern cities. In addition, they tried to understand how the society perceives religious subjects based on the texts in the holy books. The lack of qualified national and religious education in Anatolian cities has reflected and affected this situation in modern cities, and this situation has been among the main reasons for all the problems children did experience.

References | Список литературы

Akad, Ö. L. (Director). (1973a). Düğün [Wedding]. Erman Film. (In Turkish).

Akad, Ö. L. (Director). (1973b). Gelin [Bride]. Erman Film. (In Turkish).

Akdağ, M. (2020). Comparison of Village Reality in Realistic Turkish Cinema with The Village Documents (1961-1971). Adıyaman University Journal of Social Sciences, 36, 638–670. https://doi.org/10.14520/adyusbd.741984

Aksoy, O. (Director). (1976). Aile Şerefi [Family Honor]. Arzu Film. (In Turkish).

Aksoy, O. (Director). (1978). Taşı Toprağı Altın Şehir [City of Gold]. Erman Film. (In Turkish).

Aksoy, O. (Director). (1979). İstanbul 79 [Istanbul 79]. Uğur Film. (In Turkish).

Ankara, E. G. (2012, April 2). Children in Turkish cinema: From exploitation to realism. Hürriyet Daily News. https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/children-in-turkish-cinema-from-exploitation-to-realism--17387

Archive of Erbeyli Primary School Student Log Book, 1933-1953. (n.d.). Erbeyli İlkokulu Öğrenci Kütük Defteri Arşiv Kayıtları.

Atiyas, İ., & Bakis, O. (2015). Structural Change and Industrial Policy in Turkey. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 51(6), 1209–1229. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2015.1080523

Başlamişli, M. (2021). US’s Attempt to Feature 1974 Cyprus Crisis Instead of Poppy Issue Regarding Embargo Decision on Turkey. Asia Minor Studies, 9(1), 695–712. https://doi.org/10.17067/asm.827640

Becerikli, R. (2018). Comparison of Child Star Movies and Canım Kardesim In Terms of the Features of Narrative And Character. Selçuk İletişim, 11(2), 321–346. https://doi.org/10.18094/josc.406300

Bila, F. (2020, May 18). Atatürk’ün attığı temele bugün hâlâ çok ihtiyacımız var [The foundation laid by Atatürk is still very much needed today]. T24. https://t24.com.tr/yazarlar/fikret-bila/ataturk-un-attigi-temele-bugun-hala-cok-ihtiyacimiz-var,26665 (In Turkish)

Caulfield, J. (2019, September 6). How to Do Thematic Analysis | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples. Scribbr. https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/thematic-analysis/

Demirağ, T. (Director). (1973). Aynı Yolun Yolcusu [Travelers on the Same Path ]. And Film. (In Turkish).

Doğan, E. (2019). Childhood In Turkish Cinema Between 1960-1970: Representation Of Childhood In Two Different Ayşecik Films. Turkish Studies, 14(2), 313–323. https://doi.org/10.7827/TurkishStudies.14945

Duru, S. (Director). (1965). Şoför Nebahat Bizde Kabahat [Driver Nebahat is to blame]. Duru Film. (In Turkish).

Duru, S. (Director). (1970). Şoför Nebahat [Driver Nebahat]. Murat Film; Uğur Film. (In Turkish).

Eğilmez, E. (Director). (1976). Hababam Sınıfı Uyanıyor [Hababam Class Awakens]. Arzu Film. (In Turkish).

Elal, M. E. (2013). The Child in Arabesque Films [Master Thesis]. Marmara University Institute of Social Sciences.

Emre, K. B. (2007). Representation Of Childhood In Aysecik Films [Master Thesis]. Anadolu University Institute of Social Sciences.

Erksan, M. (Director). (1971). Feride [Feride]. Saner Film. (In Turkish).

Göreç, E. (Director). (1973). Öksüzler [Orphans]. Er Film. (In Turkish).

Göreç, E., & Güney, Y. (Directors). (1974). Endişe [Anxiety]. Unknown. (In Turkish).

Gülgen, M. (Director). (1979). İnsanları Seveceksin [You Will Love People]. Gülgen Film; Piza Film. (In Turkish).

Güney, Y. (Director). (1968). Seyyit Han: Toprağın Gelini [Sayyid Khan Bride of the Land]. Gülgen Film. (In Turkish).

Güney, Y. (Director). (1971). Ağıt [Requiem]. Akün Film; Güney Film. (In Turkish).

Güney, Y. (Director). (1974). Arkadaş [Friend]. Güney Film. (In Turkish).

Hamsici, M. (Director). (2018). Istanbul and Bristol in 1971 through the eyes of two children. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=duPOvbArvPU

İnanoğlu, T. (Director). (2011). Yumurcak Köprüaltı Çocuğu [Yumurcak Under the Bridge]. Erler Film (In Turkish).

Irmak, Ç. (Director). (2011). Dedemin İnsanları [My Grandfather’s People]. Ay Yapım. (In Turkish).

Jöntürk, R. (Director). (1976). Yarınsız Adam [Man Without Tomorrow]. Kalkavan Film. (In Turkish).

Jöntürk, R. (Director). (1977). Satılmış Adam [Sold Out Man]. Sezer Film. (In Turkish).

Kaçmaz, M. Y. (2020). The evaluation of the Hababam Sınıfı films from the point of values education [Unpublished Master dissertation]. Sivas University.

Kazgan, G. (2014). Türkiye’nin 1970’li Yılları: Öngörül(e)meyen Küresel Olaylar [Turkey in the 1970s: Unforeseen Global Events]. In R. F. Barbaros & E. J. Zurcher (Eds.), 70’li Yıllarda Türkiye [Turkey in the 70s] (pp. 11–30). Efil Yayınevi. (In Turkish).

Kiger, M. E., & Varpio, L. (2020). Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Medical Teacher, 42(8), 846–854. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030

Ökten, Z. (Director). (1974). Sürü [Herd]. Güney Film. (In Turkish).

Ökten, Z. (Director). (1977). Çöpçüler Kralı [King of Scavengers]. Arzu Film. (In Turkish).

Orbey, E. (Director). (1975). Bizim Aile [Our Family]. Arzu Film. (In Turkish).

Pehlivan, B. (2007). Yeşilçam Melodramatic Imagination and Its Influence on the NewTurkish Cinema [Unpublished Master dissertation]. Sabancı University.

Refiğ, H. (Director). (1969). Bir Türk’e Gönül Verdim [I set my heart on a Turk]. Erman Film. (In Turkish).

Seden, O. F. (Director). (1977). Meryem ve Oğulları [Mary and Her Sons]. Erman Film. (In Turkish).

Seden, O. F. (Director). (1978). Yüz Numaralı Adam [Man Number One Hundred]. Çan Film. (In Turkish).

Şentürk, R. (2020). The Periodization Problem in Writing the Turkish Cinema History. Intermedia International E-journal, 7(13), Article 13. https://doi.org/10.21645/intermedia.2020.81

Toptan, K., & Hacıoğlu, E. G. (2017). Ağabey Köksal Toptan [Big brother Köksal Toptan]. Bülent Ecevit Üniversitesi. (In Turkish).

Unicef. (2022, January 22). History. https://www.unicefturk.org/yazi/tarihce

Yağbasan, M., & Ateş, U. (2018). Family Representation in Turkish Cinema in the Periods Of Pre-1980 And Post-2000. Akademik Bakış Uluslararası Hakemli Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 67, 26–40.

Yıldırım, T. (2015). Sinema Tutkusu 1 [Passion for Cinema 1]. Doğu Batı Düşünce Dergisi, 18, 72. (In Turkish).

Yılmaz, A. (Director). (1964). Keşanlı Ali Destanı [The Epic of Kashanli Ali]. Gün Film. (In Turkish).

Yılmaz, A. (Director). (1966). Ah Güzel İstanbul [Ah Beautiful Istanbul]. Be-Ya Film. (In Turkish).

1Atıf Yılmaz, Lütfi Ömer Akad, Yılmaz Güney, Turgut Demirağ, Ali Özgentürk, Zeki Ökten, Ömer Kavur, Erden Kıral, Tunç Okan, Şerif Gören, etc.